Auto Armageddon? Why the EV revolution has sparked a car industry crisis

A perfect storm?

The world’s established carmakers are at a fork in the road. While they ponder what route to follow, brand-new upstarts are tailgating them aggressively, looking for an opportunity to overtake. It seems 2025 will be remembered as a very tough year for some household names.

In Europe, companies have lost up to half their value. Despite President Trump’s protectionism, the situation is also difficult in the United States where legacy manufacturers are struggling to implement new technologies and stake a claim to the future. Meanwhile, China’s car industry is surging ahead, thanks to a raft of new homegrown brands, plentiful raw materials and burgeoning EV sales.

With the automotive sector crucial to many countries’ wider economic success, the stakes could scarcely be higher. Read on to discover the trends upending the industry and find out which automakers are en route to a bright future and which ones are stuck in a jam.

All dollar amounts in US dollars

Trends: phasing out fossil fuels

Several new trends define our motoring future. Most significant is that electric vehicles (EVs) will likely become the norm as fossil fuel internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles decline in number. This poses challenges to the established industry, which is having to redesign its manufacturing and develop skills in new technologies, even as it grapples with the high fixed costs of older factories and working practices.

Pure EVs can cost up to 25% more to make, and they’re often less profitable than ICE or hybrid vehicles. This doesn’t affect big, high-value cars as much, but it makes it harder for legacy companies to offer small, affordable mass-market vehicles. The withdrawal of subsidised prices in some countries has exposed this issue even more.

Meanwhile, although the International Energy Agency expects global sales of some 20 million EVs this year – over a quarter of the total – the geographical distribution remains uneven. In some countries, the higher cost of EVs, combined with inadequate public recharging facilities and consequent ‘range anxiety’, means customer interest has stalled.

Trends: EV mandates

A number of countries and US states have set a date for banning new ICE cars in a bid to tackle climate change. Some also have mandatory targets for adopting EVs. For instance, the United Kingdom requires manufacturers to sell an increasing percentage of them each year between now and 2030 or face steep fines.

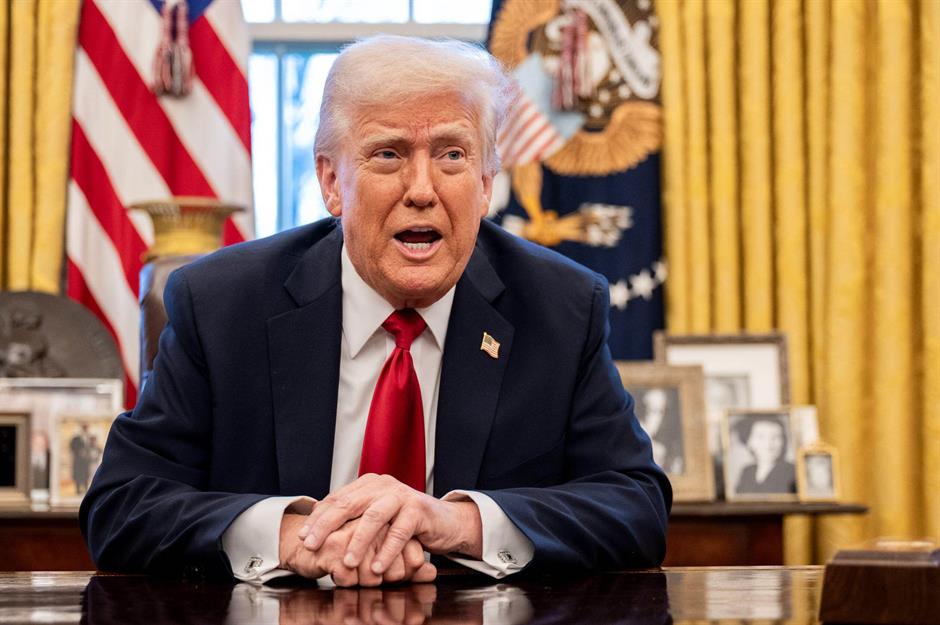

Carmakers can find these mandates too burdensome. Ditto some national leaders, with Italy’s leader Georgia Meloni having described them as self-destructive. One problem is that early subsidies to encourage EV sales are now being withdrawn. In the US, President Trump is removing a $7,500 (£5.5k) top-up that was available under Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act. However, many consumers can’t afford the full price.

Forced to sell a product that isn't always in high demand, the car industry has to offer generous EV discounts that eat into profits or ration supplies of their more lucrative ICE vehicles. In Europe, some companies have added up to €500 ($568/£420) to petrol models, but this then risks a sales slump across the board.

Sponsored Content

Trends: battery power

There are various types of EV, including the plug-in hybrid (PHEV) and fuel cell EV (FCEV). Ultimately, the norm will probably be the battery electric vehicle (BEV). This presents further challenges for legacy carmakers.

To make BEVs efficiently, assembly lines must be located close to battery factories because the immense weight of EV power packs means it’s hard to transport high numbers of them over long distances. But, especially in Europe, battery manufacture hasn’t yet scaled up to the industry’s requirements. Some big ventures like Sweden’s Northvolt and the UK’s Britishvolt have gone bust.

While global battery production will expand in the future, China is currently outpacing the West. It’s pioneering cells that can recharge faster, hold more charge and perform better in cold weather. The People’s Republic also dominates the supply chain of raw materials for EV batteries, has low energy prices and sometimes subsidises its manufacturers. In the BEV race, all this puts Chinese companies in pole position.

Trends: connectivity

The motor car has essentially been the same for over 100 years: a metal box on wheels with an engine, controlled by the driver. Now even that is about to change as connected technology and the Internet of Things (IoT) take over. Cars will talk to other devices such as traffic signals, satnavs or other cars, improving journeys and enabling occupants to stay online while mobile. Tomorrow’s cars will be computers on wheels.

All this could be great for consumers who'll have a wealth of communication, driver assistance and a more personalised experience at their fingertips. However, it will demand ever-increasing levels of digital specialism that legacy carmakers don’t necessarily have. Expect to see more and more partnerships between vehicle builders and technology companies. However, the advantage could go to newer automotive firms that are digital-first and can offer bespoke IT solutions.

Trends: self-driving cars

There have been some embarrassing hiccups, but industry analysts still insist that self-driving cars will be routine... one day. In the meantime, some experimental projects are operating, and semi-autonomous driver assistance, such as Tesla’s Autopilot function, are growing ever more sophisticated.

Yet again, this innovation entails huge investment in areas that vehicle builders might not be familiar with. Artificial Intelligence, sensing and cutting-edge software are all outside the usual capabilities of carmakers, who must therefore work with third-party digital experts. However, this is less efficient than new, so-called vertically integrated firms, where everything is in-house and bespoke, designed for the task at hand.

The natural trailblazers for autonomous vehicles would seem to be tech companies; as electric drivetrains make the mechanics of a car more straightforward, there will probably be less need to prioritise conventional engineering.

Sponsored Content

Trends: new business models

We might not even use cars in the same way before long. A Deloitte study suggests young people are becoming less enthusiastic about owning a vehicle or leasing one long-term. It found that they prefer the convenience and predictable costs of subscription and sharing services instead. The car makers of tomorrow might offer mobility through services like hourly rentals as much as through sales.

That would undermine an established industry pattern of operating via dealerships. Currently, these offer servicing, spare parts and extended warranties on behalf of manufacturers – a lucrative sideline which would disappear if people turned their back on the ownership model.

In fact, even if significant numbers of motorists continue to own cars, the maintenance and dealership business seems set to crash. That’s because EVs have as little as 40% of the servicing needs of an ICE car, thanks to their mechanical simplicity. Meanwhile, sales could easily go online with a direct buyer-to-manufacturer relationship and custom manufacturing, eliminating the middleman altogether.

Trends: tariffs

So far, 2025 is turning out to be a year of economic turmoil and the automotive sector is among the most exposed of any industry. In April, President Trump imposed a 25% tariff on all cars imported into the United States and he’s since threatened even more – mooting up to 50% on EU vehicles. European states like Germany fear a collapse in American sales, which in 2023 constituted around 15% of the country’s entire exports. Meanwhile, EVs from China already suffer an additional 100% US tariff under a Biden-era law which has essentially locked them out of the stateside market.

Europe is also turning its back on free trade. It’s slapped a 10% duty on all cars and up to 45% on BEVs coming from China. Again, Germany’s the most worried and has officially opposed the policy because of potentially ruinous Chinese retaliation.

Amid all the volatility, countries are frantically negotiating, trying to limit the damage, while car companies also urgently reorganise – with Chinese automakers setting up factories within overseas markets and Europeans reminding President Trump that they’re responsible for thousands of American jobs as well as those back home.

So, with all these challenges in mind, how are some of the biggest carmakers performing? Read on to find out.

Volkswagen

The world’s biggest carmaker by revenue, Volkswagen Group has expanded over the years to include the eponymous VW plus brands like Audi, Seat and Skoda. It became a byword for mass-producing cars quickly and economically. But it’s now facing serious difficulties.

VW's marques are highly exposed to the US tariff threats, to imminent internal combustion engine bans in Europe and to domestic competition in China, which accounts for a third of their sales. The group’s shifting half a million fewer units than before the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s about two factories’ worth. Profits for the first quarter of this year have crashed 37% on the same period last year.

In response, VW is mothballing EV factories and has only narrowly averted plant closures in its native Germany by wringing steep concessions from staff. Over 35,000 jobs will go by 2030 as part of efforts to save some €15 billion ($17bn/£12.6bn), while the workers who are left will give up bonuses and other payments. As VW accounts for nearly 40% of Germany’s car workers, it’s a bellwether for the entire country. Sadly, the forecast is very unsettled.

Sponsored Content

Toyota

The world’s largest car manufacturer by production volume with over 10 million sales a year, Japan’s Toyota is an electric pioneer, having introduced the first ever mass-produced hybrid, the Prius, back in 1997. Yet it’s become something of an outlier, more cautious about going all-electric than many rivals.

Chairman and grandson of the company’s founder, Akio Toyoda, has argued that an exclusively electric future would mean job losses among Japan’s five million auto workers, many of whom specialise in ICE technology. Instead, Toyota’s spent more time adding hybrid options to its models. It’s also been open to the possibilities of hydrogen power.

This approach attempts to cover all bases; the company might be able to jump in any direction as the most successful new technology becomes apparent. Hedging its bets, in 2027 it will begin operations at a new Chinese battery and BEV assembly plant. For now, the ‘wait and see’ strategy seems to be working as well as anyone else’s. 9Nevertheless, Toyota says US tariffs cost it $1.3 billion (£960m) in April and May alone, while Chinese competition, a stronger Yen and higher materials costs have added to an expected 21% profit decline for this year. As CEO Koji Sato says, the future is “difficult to forecast”.

Hyundai

Korea’s Hyundai is also playing a waiting game. The company has apparently accepted that BEVs will dominate the market in the future, but until the public recharging infrastructure is in place and battery costs fall, it’s decided to hedge its bets with a strategy it’s called 'The Hyundai Way'. This will focus on hybrids while also gently expanding the fully electric lineup.

Planned innovations include what Hyundai calls an Extended Range EV, or EREV. This will be driven by an electric motor like a conventional BEV but also feature a small petrol engine to recharge the battery. It should have a range of around 900km, and Hyundai will assemble it in both the US and China, no doubt hoping to avoid tariff headwinds. In fact, in March it announced $20 billion (£15bn) of American investment including a $5.8 billion (£4.3bn) steel plant in Louisiana. President Trump lauded the plans, saying they prove that his tariffs are effective at reshoring jobs.

Stellantis

Last year was rough for Stellantis. Profits slumped, and its shares lost almost half their value. This year is not much better, with net revenues in the first quarter reported to be 14% down on the same period twelve months earlier. What’s gone wrong?

Stellantis was run by Carlos Tavares (pictured), who described himself as a ‘performance psychopath’. Under his management, the company traded aggressively, making bumper profits. However, car makers tend to record sales according to wholesale deliveries. And while the dealerships bought cars, retail customers didn’t follow suit. As a result, Stellantis has accumulated massive inventories of unsold stock, especially in the US. With tariffs now adding to its problems, it’s taken the unusual step of withdrawing financial guidance for investors, while Tavares has since left the company.

As with other companies, Stellantis brands are struggling with the transition to EVs. Fiat’s electric 500e has seen production slowed or stopped several times, while an ICE van factory in Luton in the UK is closing. The company says that’s partly because of Britain’s EV mandate. On the plus side, Stellantis is investing $75 million (£55m) in a company called Factorial which makes potentially game-changing solid-state batteries.

Sponsored Content

General Motors

Detroit-based GM had planned a swift exit from making combustion engines and still has a declared aim of eliminating tailpipe emissions from its cars by 2035. However, early in 2024, CEO Mary Barra told investors that petrol-electric hybrids would be a stepping stone to this goal. GM is responding to weak American demand for BEVs as drivers worry about range, high prices, and the extent of public recharging facilities.

Meanwhile, if electric powertrains are a headache for GM, other new technology has been too painful to bear. The company stopped funding its Cruise autonomous taxi subsidiary following an accident in 2023 when a pedestrian was dragged underneath one of the self-driving vehicles. GM had hoped Cruise would return revenues of up to $50 billion (£37bn) a year by 2030.

In China, too, the company is facing headwinds. It’s partnered there with SAIC but its Chinese ventures made a loss of $347 million (£257m) in the first nine months of 2024 compared with a profit of about the same size the previous year. GM as a whole remains in the black, but like many legacy carmakers, it’s facing challenges on multiple fronts. Importing up to 55% of its US stock, it says tariffs could cost it $4-5 billion (£3–3.7bn).

SAIC

Shanghai-based SAIC is the largest of China’s state-owned car manufacturers, having scaled up within the world’s largest single market. It’s already a top 10 manufacturer by volume, responsible for making some five million vehicles, including brands like MG, Maxus and Roewe. And it’s now launched itself on the world stage.

SAIC’s government ties have made it a prime target for protectionists in America, and in Europe, where its cars attract the highest tariffs of all – over 45%. But it’s determined to be a big global exporter nevertheless. To get around the trade barriers, it's begun manufacturing outside of China. For instance, a new MG plant in Thailand will source at least 40% of parts locally, so its output is technically Thai and not Chinese. There will be factories in Europe too. Meanwhile, SAIC enables Western companies GM and Volkswagen to sell their products in China through joint ventures there.

As for the cars themselves, they’re usually electric but highly affordable, and they often undercut Western-made models. They benefit from China’s dominance of the battery industry. A new MG that’s hitting the forecourts this year features a partly solid-state battery that's both lighter and more powerful than the conventional lithium-ion version and could offer a range of up to 1,000km (621m).

Ford

By contrast, Ford has had too few customers for its all-electric vehicles. The Michigan-based giant had expected to sell two million a year by 2026, but it’s now scaling back these plans after its electric business lost some $2.5 billion (£1.85bn).

In America, Ford scrapped a planned all-electric large SUV and postponed a new electric pickup truck until 2027. It’s put a new EV factory in Tennessee on ice and will reduce capital spending on BEVs from 40% to 30% of its investment budget. It will concentrate more on hybrid powertrains instead. Ford says it’s responding to customer demand, but it also hopes that by taking the transition to pure electric more slowly it can take advantage of forthcoming advances in battery technology. It’s moving some battery production from Poland to the US. President Trump’s dislike of nudging drivers into EVs may help.

When it comes to trade restrictions, Ford is also less exposed than some companies. It makes 80% of its American products within the US, but could still suffer from 25% tariffs on imported car parts and expects a $2.5 billion (£1.85bn) hit this year, though it could offset some of that. Ford says it will need to raise prices on some of its Mexican-made models by up to $2,000 (£1.5k).

Sponsored Content

Honda

Japan’s Honda has seen net profits slump by almost a quarter amid this year’s tariff volatility, and among other measures, it's reshoring production of its new Civic model to the US from Mexico. Meanwhile, the company aims to sell only electric cars by 2040 and plans to spend the equivalent of nearly $70 billion (£52bn) on electrification over the next six years. But it’s also keeping its options open. CEO Toshihiro Mibe says that if demand for BEVs does not improve, the company still has the ability to hold off some of the investment.

Whatever happens with its drivetrains, Honda wants to up its manufacturing game to match super-efficient newcomers like Tesla and Chinese automakers. Among other innovations, it will introduce so-called gigacasting – casting giant components from a single piece of metal – and megacasting, which involves even bigger components.

Perhaps the biggest recent development for Honda was the possibility of merging with fellow Japanese automaker Nissan. The two were negotiating and hoping to share resources so they could take on Chinese competition. In February, they called off the deal, but the very fact they considered it shows how even Japan’s once invincible carmakers must think the unthinkable to adapt to the new automotive landscape.

Nissan

Honda’s would-be partner Nissan is a troubled carmaker. Its profits have fallen sharply off the back of a sales slump in the key markets of China and the US. It’s carrying record debt and hasn't kept pace with rivals in developing hybrid and electric vehicles, reporting a loss of $4.5 billion (£3.3bn) for the last financial year.

The planned recovery includes slashing costs by a whopping $3.4 billion (£2.5bn) by 2028 and radically restructuring the business. Some 20,000 jobs will disappear – around 15% of the company's global workforce – and seven of its 17 factories will close, including at least one in Japan. Plans for a new battery plant there will also be scrapped.

Nissan was an early adopter of electric cars with its Leaf BEV (pictured), but today its lineup has stalled, crucially lacking a PHEV offer in the United States. A deal to merge with Honda to make the world’s third-largest automaker might have helped, but as mentioned, it broke down earlier this year. And Nissan was already suffering turmoil after the spectacular downfall of its celebrated former CEO, Carlos Ghosn, in 2017. New leader Ivan Epinosa, who took charge in April, says the company has “a mountain to climb”.

BYD

Overall, 2024 was a great year for BYD. It enjoyed revenues of $107 billion (£79bn) after selling 41% more vehicles than in 2023 and finally surpassing Tesla. So far, this year looks better still. The company has become the biggest EV maker, and in what’s been described as a watershed moment, it marginally outsold Tesla even in Europe in April. It plans to double foreign sales in 2025 and so presents a serious challenge to Western manufacturers struggling to keep prices down. Its smallest car in China, the Seagull, is now available as the Dolphin Surf, selling for as little as €23,000 ($26k/£19k).

BYD’s winning combination is technology and low prices. Its 'God’s Eye' advanced driver assistance is included at no extra cost to buyers, even on entry-level models, and the company says it’s developed new battery technology that will offer 250 miles of charge in just five minutes. It’s also notable that, as well as pure EVs, BYD produces hybrid cars, which attract lower tariffs in the European Union.

White-hot competition in China means BYD can’t afford to be complacent though. Desperate to preserve its domestic market lead, it’s reported to have demanded 10% price reductions from some suppliers. And of course, as a Chinese EV maker, it’s still locked out of the American market. For now.

Sponsored Content

BMW

Even several years ago, when most European carmakers were convinced of an imminent all-electric future, there was one refusenik. BMW preferred its so-called ‘power of choice’, which offered customers any drivetrain. Most of its ‘platforms’ – the vehicles’ technical foundations – were multi-energy rather than exclusively for a single power source. As BEV sales now plateau in some markets and grow in others, that flexibility seems to have paid off. Profits may be down a quarter so far this year thanks to tariffs and Chinese competition, but they’re in line with expectations.

The company’s evolution towards electric cars progresses, with BMW aiming for EVs to make up half its sales by 2030. This year sees the launch of its versatile Neue Klasse platforms, designed primarily for battery power. Six new BEVs will appear, using in-house designed batteries that promise longer range and faster charging. Most sales growth in future will be from the electric models.

By retaining diversity, BMW’s bought itself time to perfect its electric offer, learning from experience and ironing out problems. It says it will stay flexible, with a place for ICE production well into the 2030s.

Mercedes-Benz

Mercedes-Benz sold almost half a million cars in the first three months of the year, but this was 4% less than the previous year, and to keep its factories busy it needs to shift more. The familiar culprits for its downturn were weaker Chinese demand and disappointing BEV sales. Now, US tariffs cloud the horizon even more. The company’s been stockpiling cars Stateside to try and hedge against them, but it’s also joined others in pulling its annual profit forecasts as earnings slumped.

As for the cars themselves: four years ago, the company predicted they’d all be electric by 2030. It’s since rowed back on that, adopting a more flexible EV policy prioritising the most receptive markets. There’s been disagreement within the company over strategy though; chief executive Ola Kaellenius preferring a focus on the most profitable luxury models to cut costs, and labour unions arguing these are precisely the cars selling less well in a fast-moving Chinese market. They favour chasing higher sales volume overall.

One initiative that might help is a partnership in China with self-driving software developer Momenta. It’s the first time Mercedes has paired with a Chinese provider of key technology, but it’s hoping this will give it an edge over rivals.

Renault

French company Renault posted record profits for 2024, thanks in part to its relatively light exposure to Chinese and US markets. Its ‘Renaulution’ strategy aims to transform the company’s business model to become, as it puts it, a next-generation automotive operation, focused more on realising value and less on mere sales volumes.

The idea is to become more vertically integrated – in other words, to have bespoke in-house supplies, while developing global vehicle platforms that can sustain different models across its marques, which include the eponymous Renault and Dacia.

However, Renault lacks the size and resources of bigger car makers, so it also partners with others like Nissan, of which it’s the largest shareholder. Its contribution to turning round the troubled carmaker is reported to have cost it some $2.4 billion (£1.8bn) in the first quarter of this year.

Sponsored Content

Tesla

Tesla has the explicit aim of being a technology company as much as a vehicle builder. As such, it’s a disrupter, bringing radical innovation and a serious challenge to established players. Enjoying high vertical integration of supplies, cutting-edge efficiency and the deep pockets of Elon Musk, it’s been riding the wave of automotive change. Recently though, it’s stalled a little.

First, it’s lost its crown as leading EV seller to China’s BYD – even in Europe. Amid recalls, high prices and a distinctly odd appearance, its flagship Cybertruck model is proving to be a flop. And perhaps most disastrously, founder Musk’s divisive political foray has alienated many customers. The result has been bad PR, protests (pictured), and even arson attacks on dealerships.

In April, Tesla reported a 71% drop in profits year on year, with EU sales having nearly halved. This would have been worse still were it not for its ability to sell regulatory credits to other manufacturers so they can sell petrol cars. It all goes to show that in today’s turbulent car industry, even the frontrunners can encounter sudden storms.

Jaguar Land Rover

The Indian conglomerate Tata owns British carmaker Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), which makes Land Rover premium SUVs and Jaguar sports sedans. JLR has had considerable success over the years, especially with its Land Rover and Range Rover brands, but like all legacy car makers, it’s having to adapt to a fast-changing world.

For Land Rover, this means fending off competition at home from its own Chinese business partner, Chery, which has entered the British market with a cheaper SUV under its upscale Jaecoo brand. Meanwhile, Land Rovers and Range Rovers depend heavily on American sales, so they’re particularly vulnerable to US protectionism, notwithstanding an outline agreement for a lower 10% tariff on a capped number of UK car exports.

As for Jaguar, it’s junking powerful petrol cars and embracing an all-electric future from next year. Future models will be aimed at a younger and even more affluent market. The new strategy has aroused controversy, with critics accusing the company of ditching its heritage and existing customer base. The idea is to sell fewer vehicles but make higher profits on each one. As they might sell for around $190,000 (£140k), it’s a bold move indeed. We’ll see whether the ‘Big Cat’ leaps toward a more exciting future… or risks extinction.

Volvo

Owned by Chinese carmaker Geely, Volvo is potentially one of the carmakers most exposed to changing trade policies, both in the US and Europe. It's shifting production of its EX30 BEV from China to Belgium, hoping to minimise tariffs. But building it in Europe could add more than $11,000 (£8k) to the price that each customer must pay. Desperate to weather the current storm, it’s also announced measures to strip out $1.87 billion (£1.4bn) of costs from its operations, including global redundancies, and joined others in ditching its 2025 financial guidance to investors, blaming too much industry volatility. In fact, it’s suspended forecasts for the next two years.

The company plans to make 90% of its cars some kind of EV by 2030, but this is a watering down of previous plans to have an electric-only lineup by that date. As with Ford and GM, part of the reason for this is the variable appetite for BEVs, as scarce public charging points and higher prices deter some customers.

Sponsored Content

Porsche

A subsidiary of Volkswagen, Porsche is one of those most badly affected by the downturn in Chinese sales, which declined 28% last year. And, due to tariffs, it’s revising its worldwide sales revenue down on previous predictions, too. The upscale German marque is also having trouble with its transition to electric drivetrains. It had aimed for 80% of its products to be EVs by the end of this decade. However, it now says it's sticking with petrol for “much longer”.

Porsche has been stung by the lacklustre uptake of EVs in some countries. One issue is that buyers of performance cars might be reluctant to give up the character and user interaction that go with a combustion engine. Batteries make vehicles heavy and – some say – less thrilling to drive. One way forward might be carbon-neutral synthetic fuels, which Porsche is trialling in Chile and hopes to make available by 2030.

Bentley

Another expensive badge under the VW umbrella, the British luxury carmaker Bentley is also finding an electric future more challenging than it first assumed. It originally planned to go all-EV by 2030. That date’s now slipped to 2035, and its first EV model won’t appear until 2026, one year later than planned.

New CEO Dr Frank-Steffen Walliser – who, incidentally, moved over from Porsche – has claimed there’s not much enthusiasm for electric cars among the present customer base. He’s also pointed out that the market for them will develop at different speeds in different countries.

That said, Bentley is still pursuing a greener future. It retired its legendary six-litre W12 petrol engine in July last year and replaced it with a hybrid petrol-electric drivetrain using a mere V8 combustion unit. The new arrangement, though emitting far less CO2, will, in fact, have even more power.

Rolls Royce

The 120-year-old British luxury marque Rolls Royce has struck an upbeat note with plans for a £300 million ($378m) investment to expand manufacturing at its famous Goodwood factory. Now owned by BMW, it has an unusual plan to survive: by offering highly customised versions of its cars to uber-wealthy buyers.

Those who commission it to adapt their purchases will pay a hefty premium to add unique features like holographic paint, works of art or even solid gold fittings, all of which will push up base prices as high as £340,000 ($459k). Needless to say, clients who can afford this level of refinement would tend to be less worried about any price hikes caused by tariffs, electric drivetrains or industrial overheads so Rolls Royce could be that rarest of things – a car company with a secure future.

That said, it produces only a few thousand vehicles each year, and though it refuses to say if it will continue to offer petrol engines after 2030, it says it has to be ready to adopt an all-electric fleet if customers – and governments – demand it.

Sponsored Content

What does the future hold?

As these examples clearly demonstrate, the legacy car industry is undergoing a massive shake-up. The biggest long-term challenges are likely to be how to electrify profitably while fending off competition from new players, especially those from China. Meanwhile, there’s the short-term emergency of simply surviving the ever-changing tariff onslaught.

If established players can’t prevail, the West could be in for a shock. The automotive sector is vital for many national economies and supports employment far beyond car factories themselves. The turmoil has already caused significant job losses in supply chains: in Germany, steelmaker Thyssenkrupp is cutting 40% of its workforce and other suppliers have axed 20,000 positions between them. The Bosch automotive division is shedding 8,000 jobs globally.

We're likely to see some dramatic changes in the years to come, with some companies merging or taking over others, and some meeting their end. Will electrification and high technology rescue sales? And what will the overall impact of trade protection be? However it pans out, the consequences will be hard to ignore. This matters for everyone.

Now discover the 30 most innovative countries in the world

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature