The Dutch East India Company's incredible rise and fall

Discover the history of the world's richest company ever

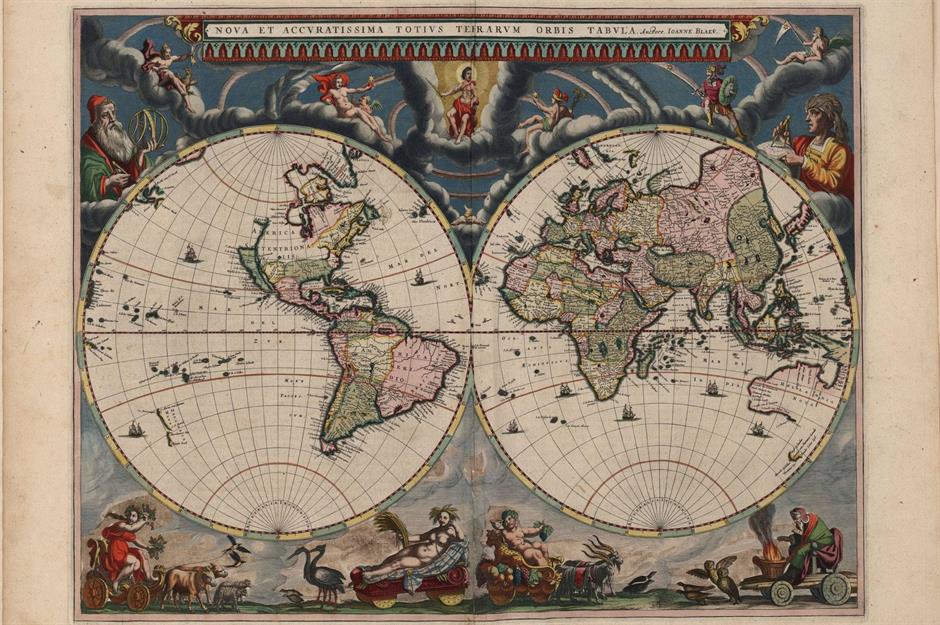

As powerful as a nation state, the Dutch East India Company sent almost a million Europeans to Asia on more than 4,700 ships and dominated global trade for almost two centuries, handling a whopping 2.5 million tons of goods. The grandfather of the modern-day corporation, the company was the first to undertake an IPO, trade transnationally, become a globally recognised brand, and more. We explore the pioneering firm's history and chart its incredible rise and fall.

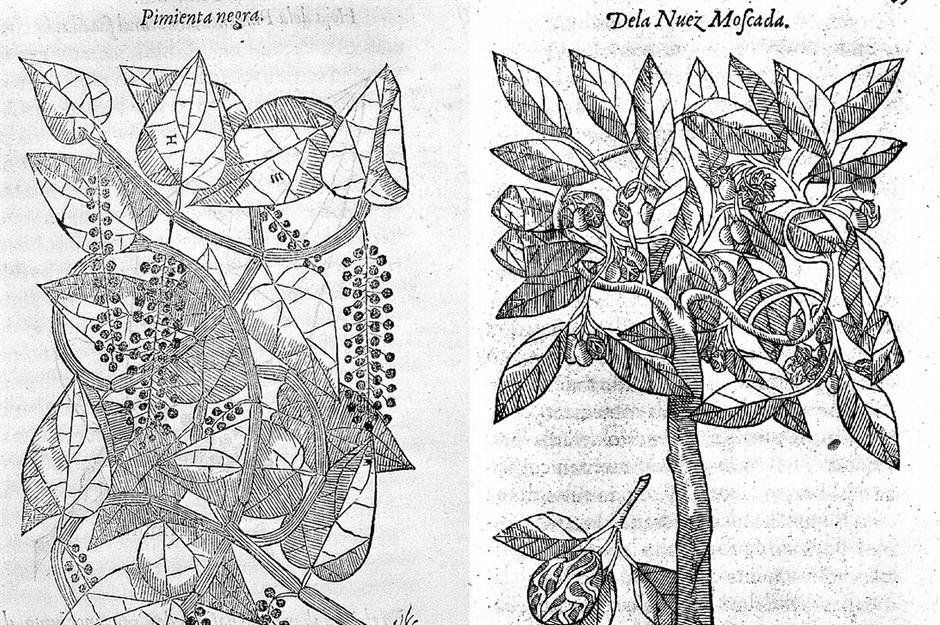

Scarce spices

Spices like pepper, cloves, nutmeg and cinnamon are widely available and cheap to buy today. Yet back in the 16th century these aromatic commodities, used for everything from medicines to food preservation, were super-rare and exceptionally valuable in Europe. At the time, a small pouch of spices could easily buy a herd of cattle or sheep.

Portuguese monopoly

The Portuguese boasted a monopoly of the international spice trade throughout the 16th century thanks to explorer Vasco da Gama, who discovered the sea route to the East Indies in the 1490s. Catholic Portugal mostly traded the commodities with the Protestant countries of Northern Europe. Yet this all changed in 1580 when Spain, which was at war with England and the Low Countries (now the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and French Flanders), united with its neighbour.

Sponsored Content

Industrial espionage

Desperate to get a foothold in the lucrative global spice trade, the newly formed Dutch Republic recruited spies such as Cornelis de Houtman, who fed back key information from Asia. The agents provided maps of 'secret' sea routes, local customs, weather conditions and intel on the Portuguese navy, which they deduced had been severely weakened. The spice trade was there for the taking.

Initial expeditions

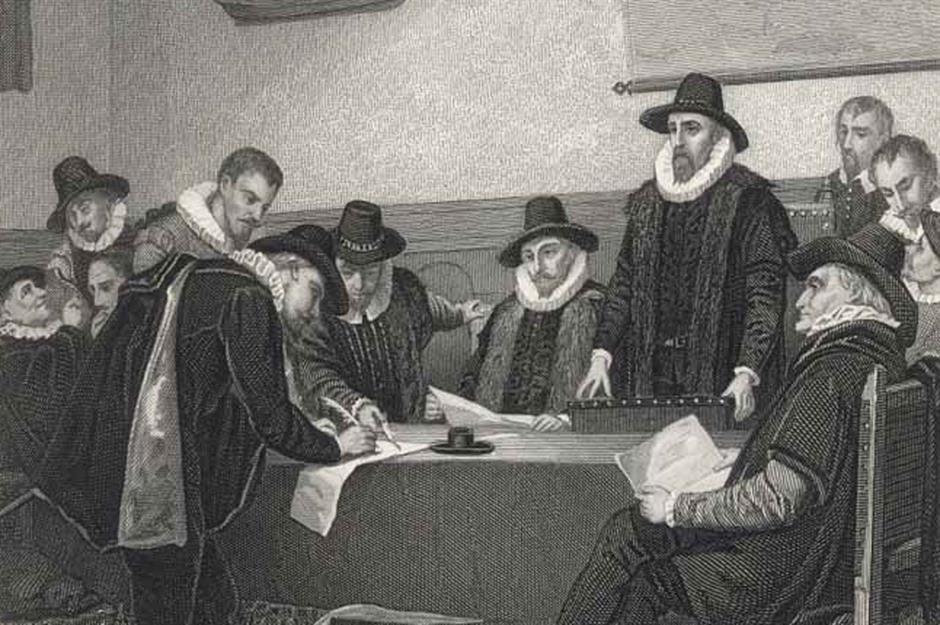

Company formation

Nevertheless, a number of Dutch companies were competing for the spice trade. As a result, prices fluctuated wildly, eating into their profits. To stabilise the risk, the Dutch Republic amalgamated the rival firms and formed a cartel in 1602, taking their cues from the English, who did much the same thing two years prior by creating the English East India Company.

Sponsored Content

Powerful firm

The Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) or Dutch East India Company as it is known in English, had start-up capital of 6.4 million guilders. To put it into context, that's roughly the value of 1,000 Amsterdam townhouses or $416 million (£314m) in today's money. The company was even allowed to erect forts, build a formidable private army and sign treaties with local rulers. From the get-go, it was more like a mini country than a company.

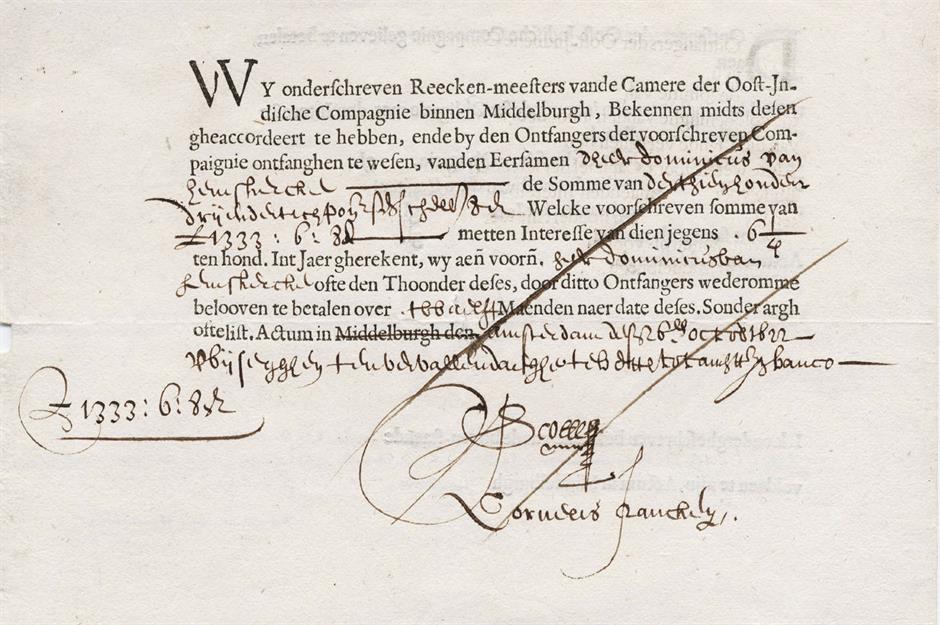

First IPO

How did it get hold of all that money in the first place? The VOC was the first company to sell stocks to the general public, conducting the world's first proper IPO in 1602 when it was trying to raise capital. The minimum investment was 3,000 guilders or £500, which works out at around $195,000 (£160k) when adjusted for inflation. As the company's profits quickly soared, it was able to pay out bountiful dividends, much to the delight of its investors.

Corporate identity

Nowadays, multinational corporations' logos, from McDonald's to Apple to Nike, make them recognisable worldwide. Yet it was the VOC that created the first internationally recognised corporate logo, when it was founded back in 1602. This gave rise to the concept of corporate identity that is integral to modern global business. Consisting of a prominent capital V with an O on the left and a C on the right, the monogram was familiar to countless people in Europe, Asia and Africa.

Sponsored Content

Early successes

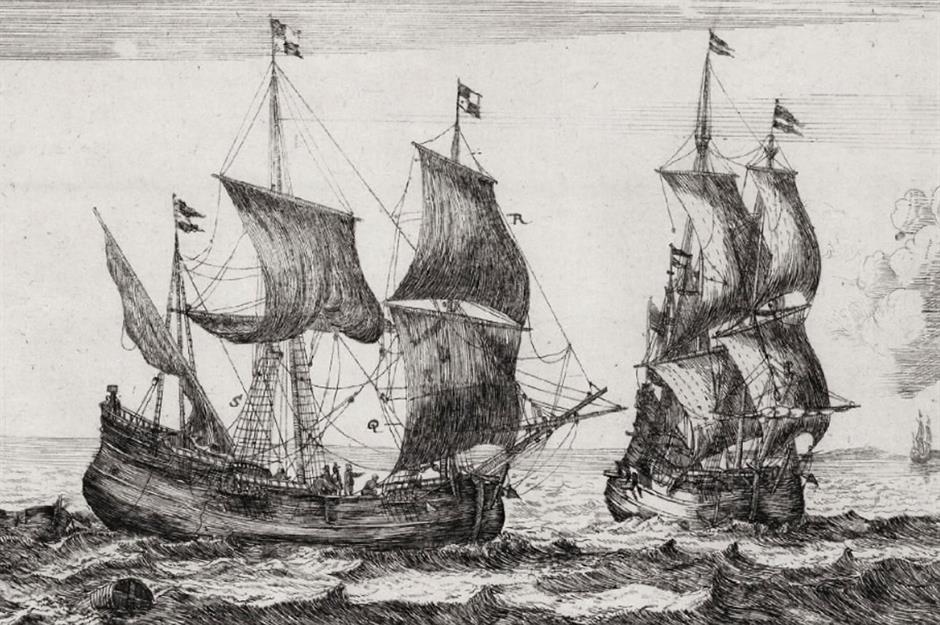

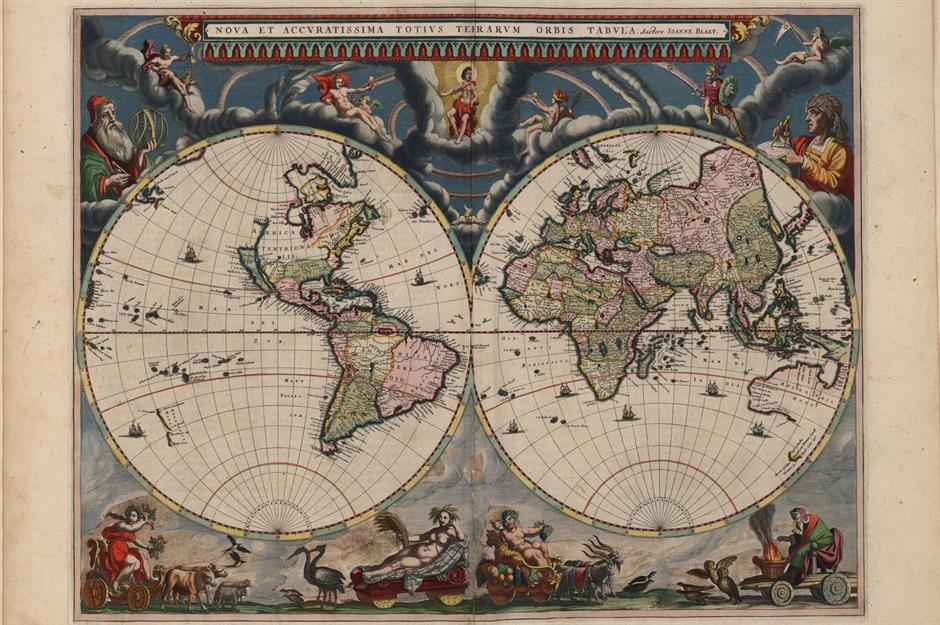

Global reach

VOC ships travelled far and wide. In 1606, the Duyfken was the first European vessel to land on the continent of Australia or Nova Hollandia as it was later named by the Dutch. Meanwhile the VOC's Halve Maen (pictured), which was famously commanded by English seafarer Henry Hudson, sailed into what is now known as Upper New York Bay in 1609.

Horrific conditions

Life at sea and in the VOC outposts was far from pleasant, however. Pay was low, discipline was brutal, disease was rife and accidents were all too frequent. Only one in three sailors who set sail with the company ever returned, and those who did tended to be malnourished, seriously ill – with scurvy, for instance, common due to lack of nutritious food onboard – or nursing life-threatening injuries.

Sponsored Content

First public company

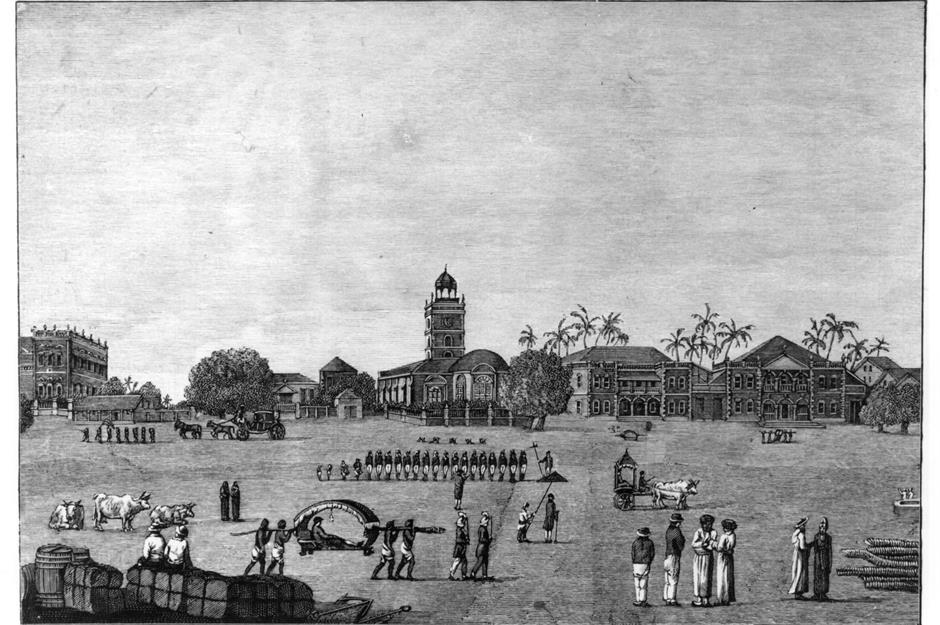

First multinational firm

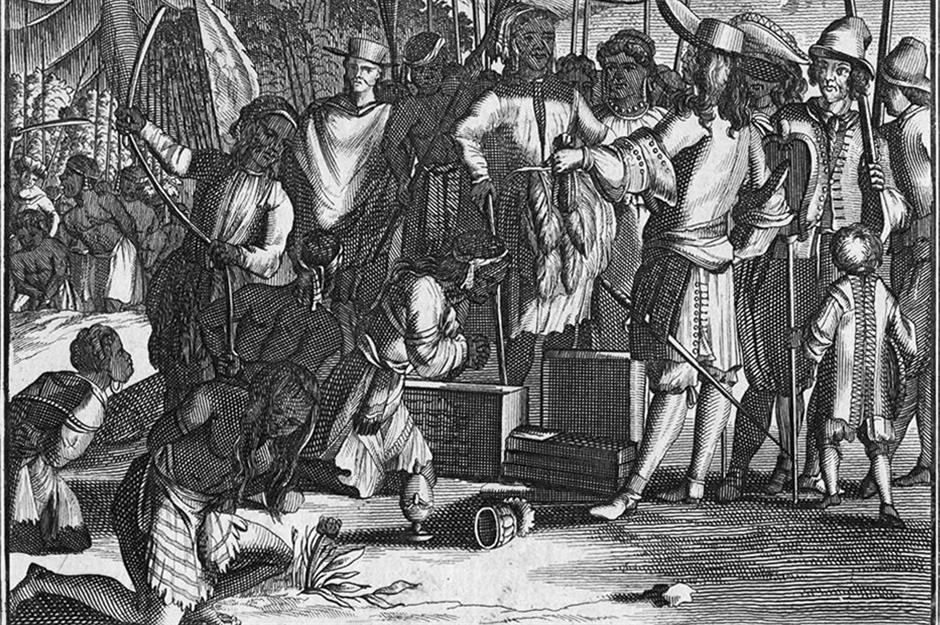

Scoring yet anther first, the VOC became the world's first multinational firm in 1619 when its Governor-General Jan Pieterszoon Coen ordered an attack on the port of Jayakarta (modern-day Jakarta). Coen and his troups razed the city to the ground, killing or banishing most of the native population. In 1621, they renamed it to Batavia, a name which derived from their Germanic tribal ancestors, and the newly-established port came under the company's rule as the VOC's Asian HQ.

Lucrative trade

A pioneer of outward direct foreign investment, the company's operations expanded significantly in Asia during the 1620s. Trading outposts were founded in Formosa (Taiwan) and Mughal Bengal in India, and profits surged at the expense of native populations. The VOC was able to sell its spices at 14 to 17 times the price it paid for them in Asia, since they were so valuable and rare in Europe.

Sponsored Content

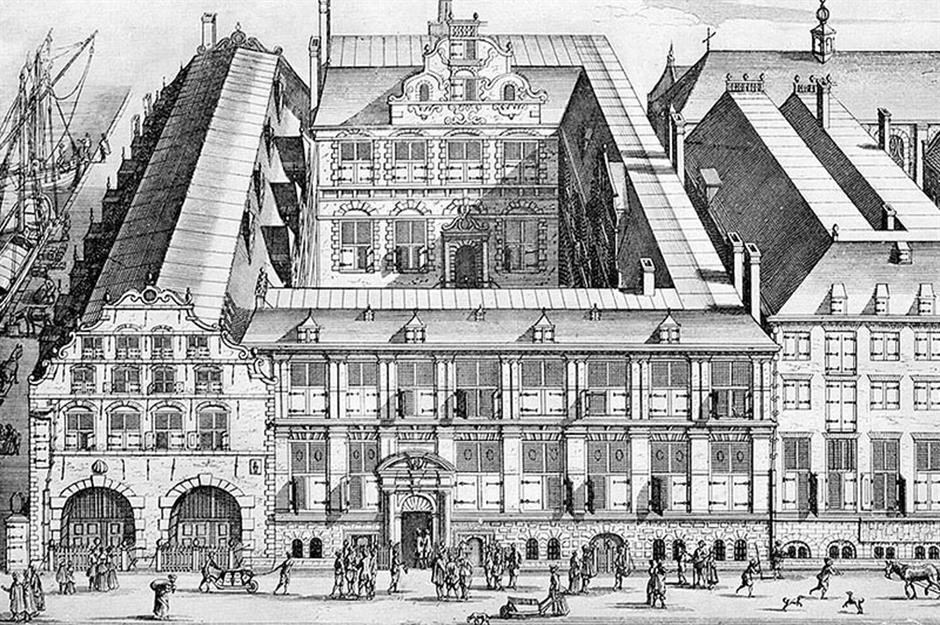

Richest city

Today, Amsterdam's elaborate, 17th century gabled houses serve as a reminder of the 'Golden Age', when the Netherlands was a world-leading economic power. During that time, Amsterdam was its most important commercial hub and the richest city in the Western world, mainly due to the success of the VOC. The city was number one for all sorts of industries, from finance to shipbuilding, and by the latter half of the 17th century its GDP per capita was four times that of Paris.

Tulip mania

The value of the VOC skyrocketed from 1634 when its ships, which carried tulip bulbs, triggered the infamous Tulip Mania, the world's first recorded speculative bubble. Everyone went crazy for the newly-fashionable flowers, and the general mania around them hiked asset prices well above their intrinsic values, pushing the company's share price up 1,200%. At the peak of the bubble, a single tulip bulb cost more than the annual income of a worker and even several houses.

Read more about Tulip Mania and The biggest economic bubbles of all time

Tulip bubble

Just before the bubble burst in 1637, the firm was worth 78 million Dutch guilders, which according to some sources is $8.2 trillion (£6.7trn) in 2019 money. That's almost as much as the combined GDPs of modern-day Germany, the UK and France, according to World Bank estimates. The VOC survived the crash and Amsterdam remained the commercial capital of the Western world, though many investors were made bankrupt.

Sponsored Content

Early expansion

Slave labour

In 1652, the VOC established a supply post at the Cape of Storms (later renamed the Cape of Good Hope) in modern-day South Africa, founding Kaapstad (Cape Town). Yet the VOC left a brutal legacy of colonial rule there. The company shipped in thousands of enslaved people from other parts of Africa and elsewhere to work the land and act as servants to the European settlers. Nomadic peoples were displaced and their grazing lands occupied, forcing them to either flee or work for the colonists, while many died of European-imported diseases like smallpox.

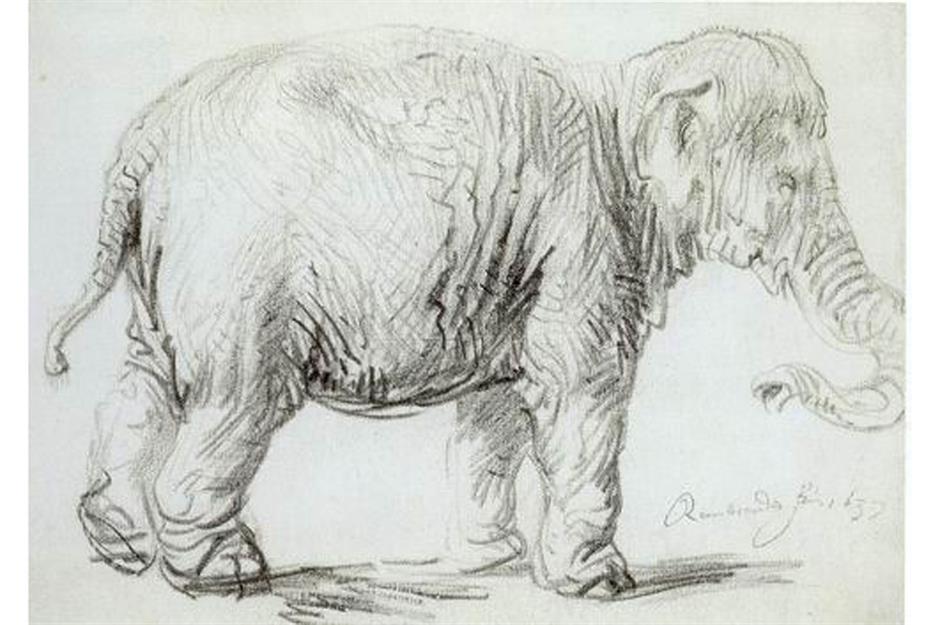

Diverse trade

The Dutch founded the South African wine industry not long after establishing its colony. In addition to wine, spices, cotton, silk and so on, the VOC traded other desirable products such as opium, sugar and tea, and even exported elephants at one time. Dutch Master Rembrandt sketched this elephant in Amsterdam in 1637. Hansken, as the animal was named, had been imported into Holland in 1633 by the VOC.

Sponsored Content

Wealthiest company

Trading system

The VOC had successfully managed to create a powerful intra-Asia trading system by this point. Gold, silver and copper from Japan were traded with Mughal Bengal (now Bangladesh and West Bengal, India), Formosa (now Taiwan) and other Asian countries, for porcelain, silk and cotton. These, in turn, were exchanged for spices from Batavia and elsewhere. The system ensured that European supplies of precious metals remained plentiful.

Golden Age ends

The Golden Age of the VOC came to an end in 1670, as competition from other European giants, including the French East India Company and the Danish East India Company, intensified. Gradually, spices and other commodities from the Caribbean and South America flooded the market. Conflict with the English also interrupted the VOC's global operations, as did a decline in trade with Japan, which introduced limits on the export of gold, silver and copper.

Sponsored Content

Expansion Age begins

From there on in, the VOC switched from trading in high-value, low-volume commodities like spices to less profitable low-value, high-volume products, such as tea, coffee, textiles and sugar. This ushered in the start of the so-called Expansion Age, which lasted until 1730. Low interest rates made this less lucrative trade possible and the company relied on debt to keep its operations up and running.

Increased debt

Still, the company doubled in size from 1680 to 1730, though profit margins had been slimmed-down. Where profits had represented 18% of total revenues during the Golden Age (1630-1670), they now represented just 10% of revenues in this later Expansion Age (1680-1730). Overheads had risen and productivity stagnated, but dividends remained generous meaning that less money was put back into the company, relatively speaking. The company's capital decreased as a consequence and its debts spiked.

China trade

Trade with China provided a boost for the company at the end of the Expansion Age, particularly trade in tea. In 1729, the VOC built a factory in the Canton province of China, allowing for direct trade with the rest of the country, despite the best efforts of the British, who were becoming increasingly antagonistic. However, the trade partnership wasn't enough to stave off the decline of the company.

Sponsored Content

Surging expenses

The VOC had become embroiled in the Javanese Wars of Succession, which took place between the company and the independent kingdom of the Sultanate of Mataram between 1677 and 1755. The wars proved to be very costly for the company. Fuelled in part by its insistence on dishing out generous dividends to investors, the VOC's debts continued to rise, which needless to say, didn't do the company's bottom line any favours.

Widespread corruption

Corruption had become rampant. VOC employees were notoriously poorly paid and working conditions were atrocious in many respects, which prompted staff to engage in theft and contraband trade in order to prop up their woeful incomes. Worse still, the appalling working conditions bred disease and led to high mortality rates among workers, which hardly helped the company's performance. From the 1790s onwards, this played a huge role in the demise of the VOC.

Death knell

To top it all off, the company had a policy of routing all trade through its Batavia HQ, which proved to be expensive and inefficient. The death knell came in 1780 with the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. The conflict was catastrophic for the VOC, which saw its fleet decimated by half and its power in Asia severely eroded. Crippled by debt, the VOC was nationalised in 1796.

Sponsored Content

Company dissolved

By this time, Napoleon had invaded the Dutch Republic and the new Batavian Republic had been declared. A complete basket case, the VOC, which was in dire financial straits, trundled on, but was liquidated by the government in 1799. Many of its former possessions were eventually claimed by the new global superpower Great Britain, and the centre of global finance moved from Amsterdam to London.

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature