50 photos of amazing worldwide wonders we’ve just discovered

The greatest discoveries of the modern world

Tikal's unknown treasures, Guatemala, 2018

The Maya settlement of Tikal in northeastern Guatemala has been studied for decades, and it’s one of the best understood sites of its kind. Or so experts thought. In 2018, new technology called LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) has allowed archaeologists to dig a little deeper. LIDAR involves lasers, which pierce through the forestland to the earth below. Based on how long it takes a beam to bounce back, scientists can map any hidden structures that exist beneath the ground. The recent findings have been extraordinary.

Tikal's unknown treasures, Guatemala, 2018

Sponsored Content

Qalatga Darband, Iraqi Kurdistan, 2017

Qalatga Darband, Iraqi Kurdistan, 2017

Roman boxing gloves, England, 2017

The archeologists at Vindolanda, a Roman archaeological site just south of Hadrian’s Wall, conduct an excavation of the park each year. In 2017, they found more than they’d bargained for. Swords, writing tablets and shoes were among the items unearthed and, most impressive of all, a pair of leather Roman boxing gloves (pictured). These curious artifacts went on display in the Vindolanda museum in February 2018.

Sponsored Content

Roman 'horseshoes', England, 2017

Another, later dig has uncovered yet more riches. The most significant find was a set of rare iron 'hipposandals', a kind of historic horseshoe. Of the four hipposandals unearthed, only one was damaged – the others remained in perfect condition. The artifacts will go on display at the Roman Army Museum in Greenhead in February 2019.

A secret structure at Petra, Jordan, 2016

Modern technology has helped researchers uncover a giant platform of a similar size to an Olympic swimming pool at the ancient city and UNESCO site of Petra. After poring over satellite and drone images, archaeologists noticed a large rectangular structure not far from the famous Treasury (pictured). It’s thought that the structure was once lined with columns, and experts muse that it could have been a holy building, or some sort of public administrative building. One thing they agree on is that they’ve never found anything similar at the site.

El Castillo’s hidden pyramid, Chichén Itzá, Mexico, 2016

Sponsored Content

El Castillo’s hidden pyramid, Chichén Itzá, Mexico, 2016

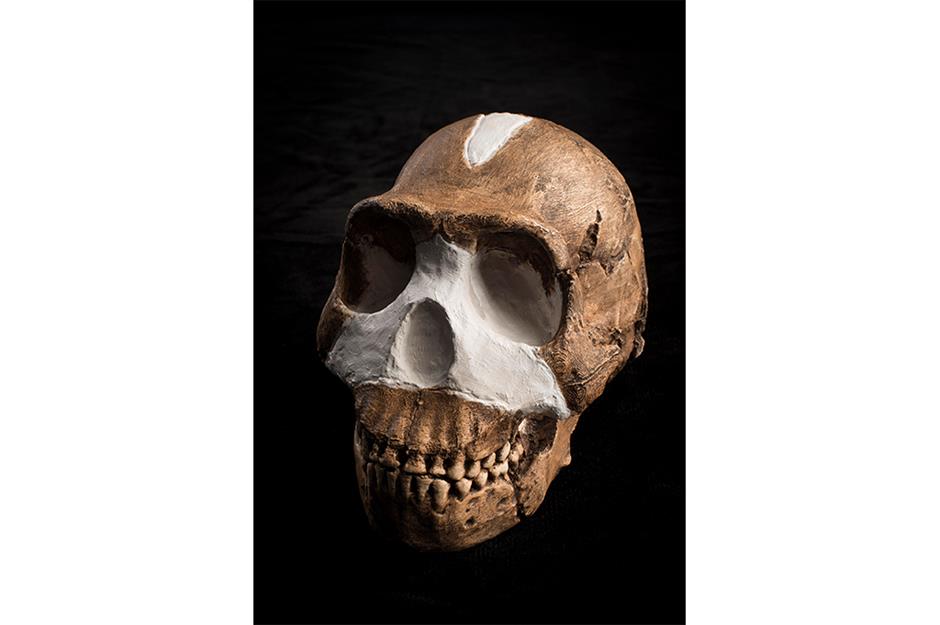

Homo naledi, South Africa, 2013

.jpg)

Homo naledi, South Africa, 2013

Sponsored Content

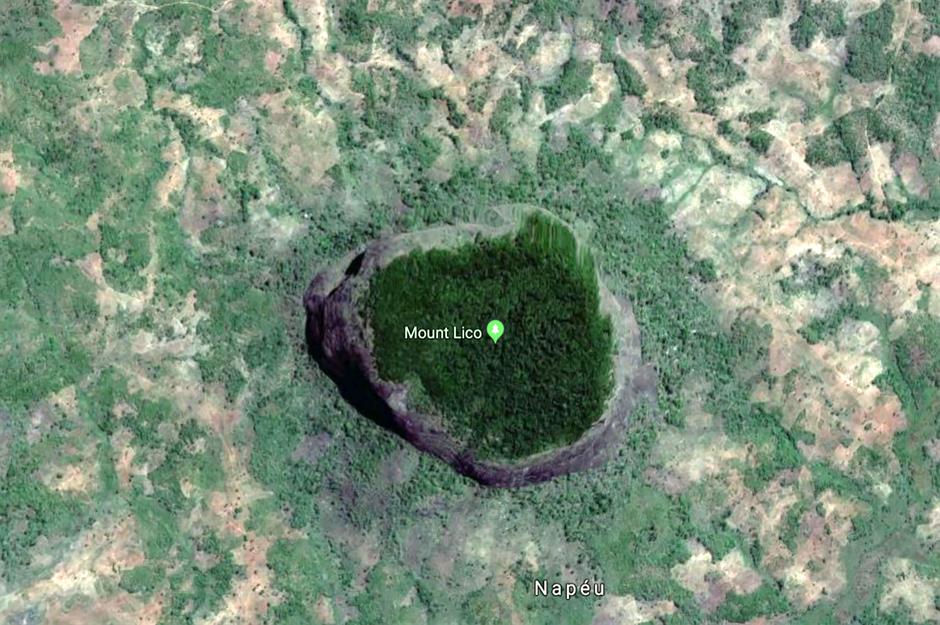

Mount Lico's secret rainforest, Mozambique, 2012

It was 2012 when researcher Dr. Julian Bayliss first spotted a rainforest atop Mozambique's 3,600-foot Mount Lico on Google Earth (pictured). Though potentially known to locals, the mountain rainforest remained virtually untouched by humans due to its remote location. In 2017, Bayliss flew a drone over the peak and confirmed the forest's existence. In May 2018, he assembled a team to scale the mountain and explore the forest properly for the first time. The expedition was a success and, though research is still underway, the team is thought to have uncovered a string of new species from small mammals to insects – already confirmed is a previously undocumented breed of butterfly.

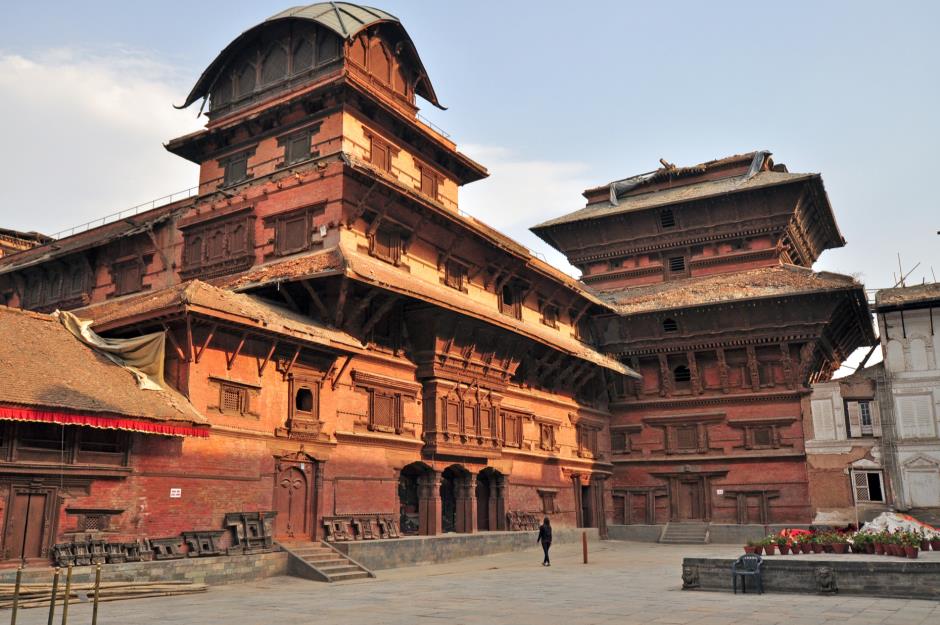

Hanuman Dhoka Palace treasures, Nepal, 2011

Padmanabhaswamy Temple treasure, India, 2011

Sponsored Content

Padmanabhaswamy Temple treasure, India, 2011

Temple of the Night Sun, Guatemala, 2010

Son Doong Cave, Vietnam, 2008

This vast cave in Vietnam’s Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park was first stumbled upon in 1999, by a farmer named Ho Khanh who took refuge from a storm in its depths. Once the storm had passed, Ho Khanh reported his discovery to the British Caving Research Association (BCRA), who happened to be in Vietnam at the time. Unfortunately, he couldn’t manage to trace his steps back to the mysterious cavern. Then, almost a decade later, Ho Khanh rediscovered the cave's entrance while hunting and alerted the BCRA once more.

Sponsored Content

Son Doong Cave, Vietnam, 2008

Son Doong Cave, Vietnam, 2008

You can visit the Son Doong Cave on an expedition with adventure tour company Oxalis, currently the only operator to visit the cavern. The tour is a five-day undertaking that includes a jungle trek, a rope climb into the cave’s entrance and two nights of camping within its depths. You'll travel with a 25-strong team of guides and safety experts. If you’ve the steel and stamina, it’s sure to be an unforgettable trip.

Must Farm, England, 2004

Archeologists have dubbed a site adjacent to a quarry in the Cambridgeshire Fens the “British Pompeii”, having unearthed what is believed to be a 3,000-year-old Bronze Age settlement. The site first came to experts’ attention when a series of wooden posts were spotted jutting out of the clay in 1999, but the first excavation didn’t happen until 2004. These early digs revealed a sword and spearheads, hinting at an early settlement. At this stage, researchers still had little idea of the scale of what they'd soon discover.

Sponsored Content

Must Farm, England, 2004

Extensive excavations (the most recent a 10-month dig beginning August 2015) revealed what experts have deemed the best-preserved Bronze Age settlement in Britain. From their multitude of discoveries, archaeologists have been able to piece together the fate of this specific ancient village, and uncover previously unknown truths about the Bronze Age peoples. Textiles, pottery and roof timbers (pictured) have all been among the finds – the latter has allowed experts to learn how a Bronze Age home would have been built.

Must Farm, England, 2004

Animal bones and fish scales (pictured) offered insights into the diet of the peoples who lived here, while fabrics gave experts a glimpse into the settlers’ clothing. Archaeologists also have enough information to deduce that the village was destroyed by a fire some six months after it was built – the village’s ruins sank into a nearby river, which is why they remain so beautifully preserved. Though there may well be more excavations in the future, experts are now busy studying the treasures exposed in their last dig, so the site is currently off-limits to the public.

The Ness of Brodgar, Scotland, 2003

Sponsored Content

The Ness of Brodgar, Scotland, 2003

The huge discovery, which predates Stonehenge, is the world’s most significant Neolithic discovery in recent history. Excavations, which are still ongoing, have discovered 20-foot-thick walls, painted stonework, pathways, pottery and more than 12 temples, all built more than 5,000 years ago. On select summer dates, you can visit the dig – find out more from the Ness of Brodgar Trust.

Selinunte, Sicily, c.2000 onwards

Selinunte, Sicily, c.2000 onwards

Sponsored Content

Selinunte, Sicily, c.2000 onwards

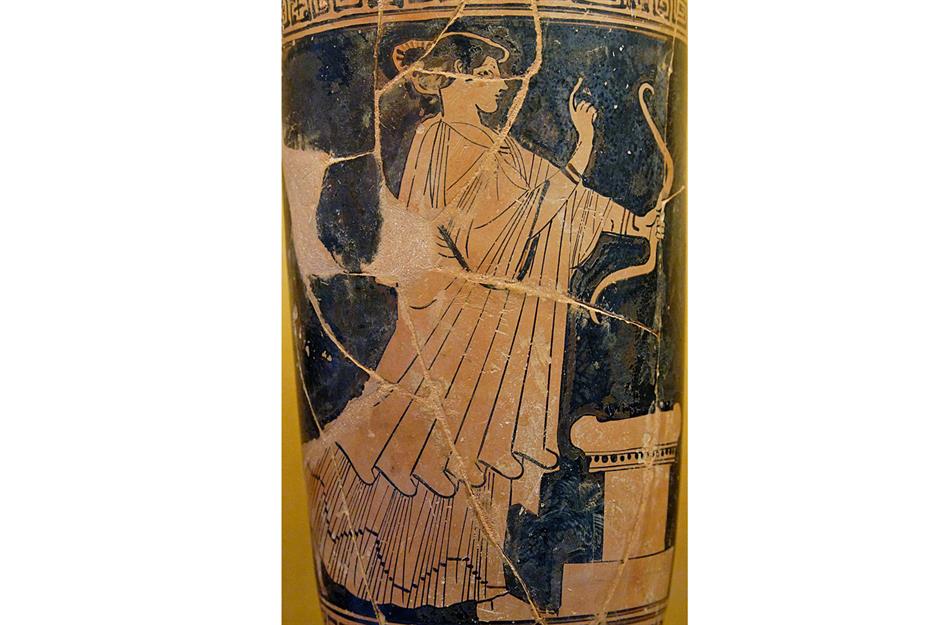

The discoveries have helped experts build a clear picture of what this kind of Greek civilization would have looked like. Researchers have exposed some 2,500 deserted houses, traced streets and discovered what they assume would have been a kind of industrial zone, where many potters are thought to have worked. Around 80 kilns and pottery workshops have been discovered, plus pigments and fragmented ceramics. Selinunte is open daily and you can book a guided tour to discover more about the site's history and the archeological work going on here.

Historic Jamestowne, Virginia, 1994

The live archeological site of Historic Jamestowne offers a detailed insight into what life was like for the 104 travelers who established the first permanent English settlement in North America in 1607. Under frequent attack by Native Americans defending their homeland, the settlers quickly built themselves a triangular fort, using logs. Since 1994, when excavations began, the remains of the original James Fort have been found, along with more than 1.5 million artifacts.

Historic Jamestowne, Virginia, 1994

Sponsored Content

Historic Jamestowne, Virginia, 1994

Gobekli Tepe, Turkey, 1994

Gobekli Tepe, Turkey, 1994

The pillars are carved with lions, scorpions and snakes, and weigh up to 60 tons. It remains a mystery how the hunter-gatherers shifted them into position, but the remarkable feat suggests society in 10,000 BC was far more developed than we thought. In early 2017, a report in Science Advances also announced the discovery of three skulls at the site, which had holes in them. It’s thought they might have been suspended in the air and that Gobekli Tepe was part of an ancient skull cult.

Sponsored Content

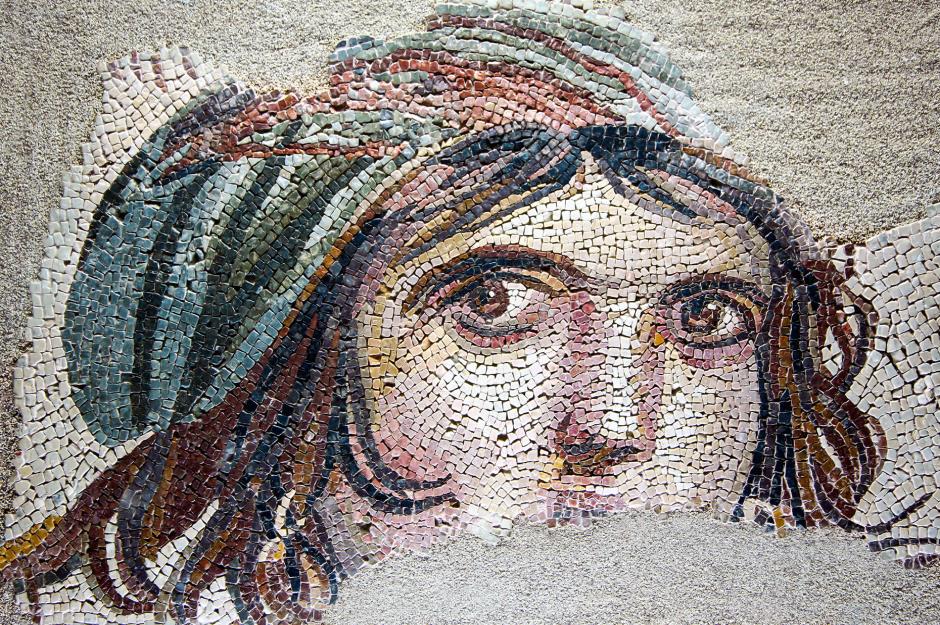

The Zeugma mosaics, Turkey, 1992

The Zeugma mosaics, Turkey, 1992

The glass floor mosaics, which were discovered in Roman villas, are now on display at the Zeugma Mosaic Museum, in Gaziantep, Turkey. Built to house them in 2011, it’s now the largest mosaic museum in the world.

The Zeugma mosaics, Turkey, 1992

Sponsored Content

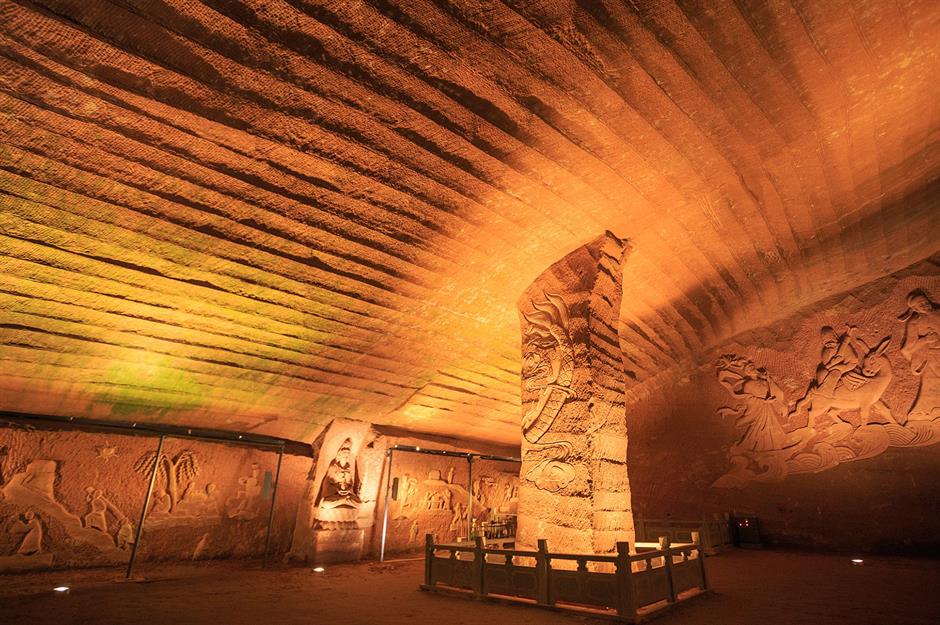

Longyou Caves, China, 1992

Longyou Caves, China, 1992

Balamku, Mexico, 1990

Sponsored Content

Balamku, Mexico, 1990

The Rosalila Temple, Honduras, 1989

The Rosalila Temple, Honduras, 1989

The temple’s inner walls were coated in soot from torches and, inside, several religious artifacts were discovered, including incense burners, stone pedestals and flint knives thought to be used in sacrifices. Today, a life-size replica of the Rosalila, which features its intricate artwork, is on display at the Sculpture Museum in Copán.

Sponsored Content

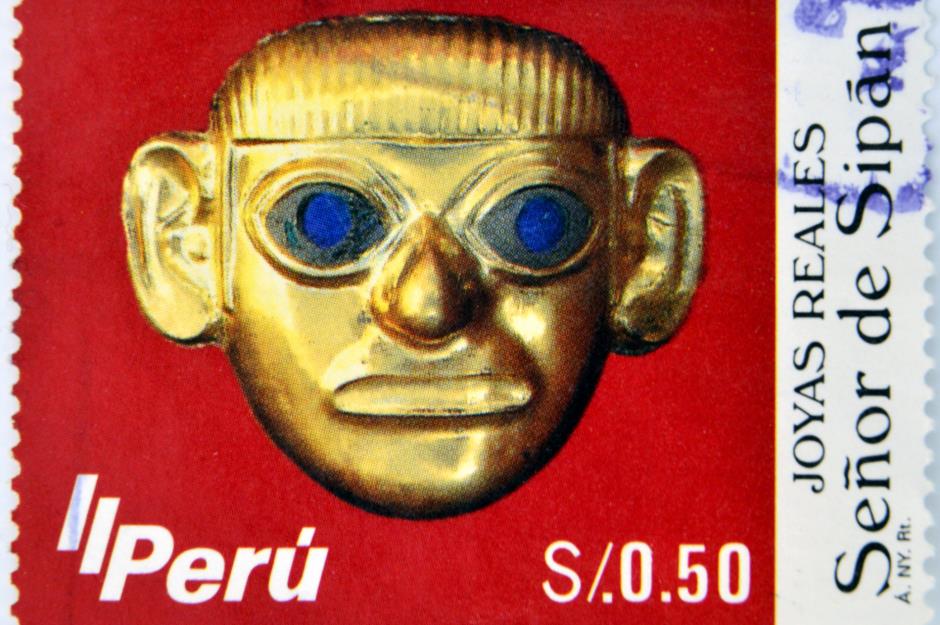

The Royal Tombs of Sipán, Peru, 1987

The Royal Tombs of Sipán, Peru, 1987

The Royal Tombs of Sipán, Peru, 1987

Today, experts believe he is an important Mochican warrior priest, now known as the Lord of Sipán. He wasn’t alone in his tomb, either. Three women, a child, two men and two llamas were also buried alongside him. It’s believed some had died previously, while others were sacrificed. You can see many of the artifacts on display at the Royal Tombs of Sipán Museum in Lambayeque, Peru.

Sponsored Content

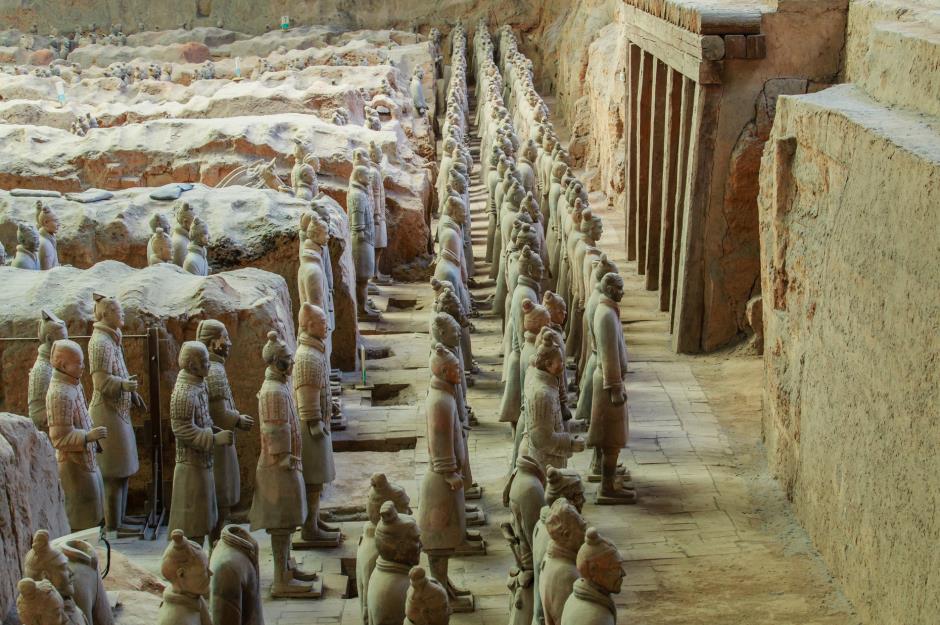

The Terracotta Army, Xi’an, China, 1974

The Terracotta Army, Xi’an, China, 1974

The Terracotta Army, Xi’an, China, 1974

It’s thought the army was created to guard the body of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, who died in 210 BC and whose tomb lies around a mile away. You can see the figures at the Terracotta Army Museum in Xi’an, in West China’s Shaanxi Province.

Sponsored Content

The Lost City, Colombia, 1972

The Lost City, Colombia, 1972

The Lost City, Colombia, 1972

Sponsored Content

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature