Vintage images reveal an American industrial era long gone

Past professions

Times change, and so too do the jobs we do and the industries we work in. Nowhere is this more apparent than in America, where some of the world’s greatest enterprises were born, flourished and then fell into decline.

Click through the gallery for astounding images of industries and lines of work that helped to shape the American story but have since fallen by the wayside…

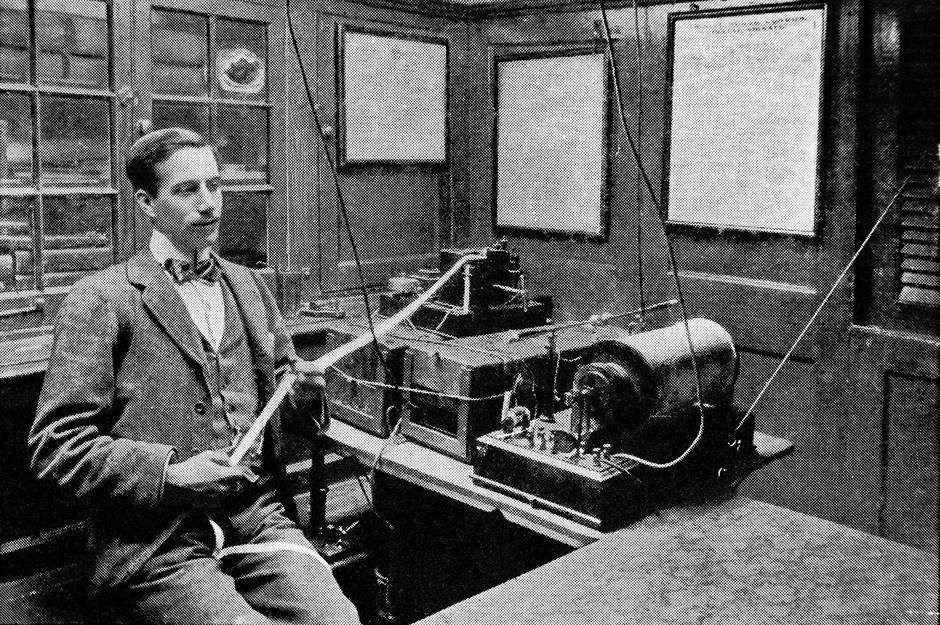

Telegraphy

The electric telegraph was one of the first telecommunications technologies of the industrial age and arguably the most far-reaching. Using a system developed by 19th-century inventors like Guglielmo Marconi (pictured) and Samuel Morse, an electric current could be sent down a wire and broken in a particular pattern, denoting letters or phrases.

At a time when it still took two days to travel to Chicago from New York City, the ability to send a message between those two cities instantaneously was revolutionary.

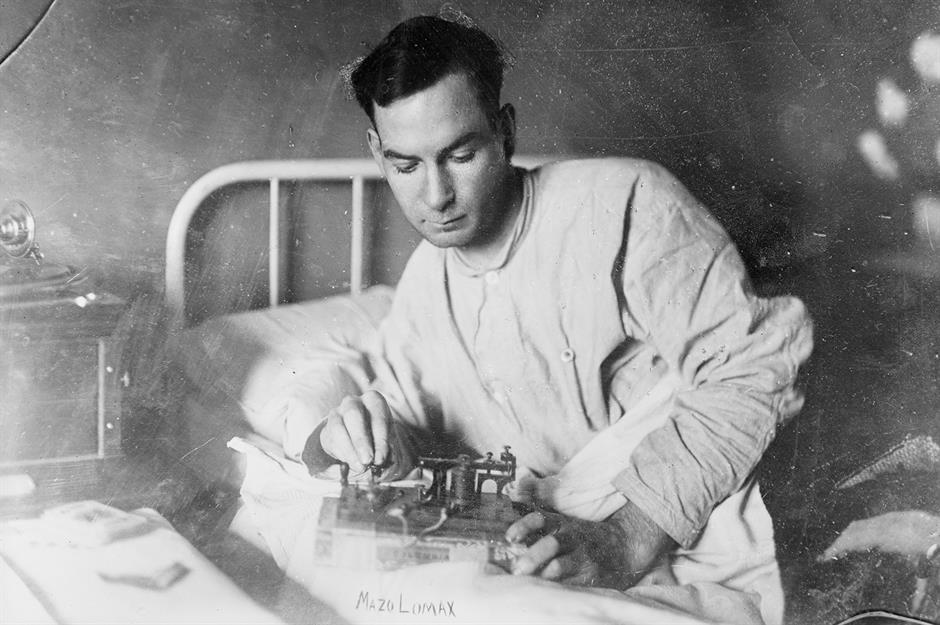

Telegraphy

The impact of being able to transmit information quickly over long distances was immediate and extraordinary. Railroads grew exponentially, financial and commodity markets boomed and information costs within and between firms plummeted.

From 1867 to 1900, the number of messages sent by Western Union alone increased from 5.8 million to 63.2 million, with the company making 30-40% profit on every dollar spent. Such was the need for telegraph operators that the American Red Cross began training wounded soldiers (pictured) to meet the demands.

Sponsored Content

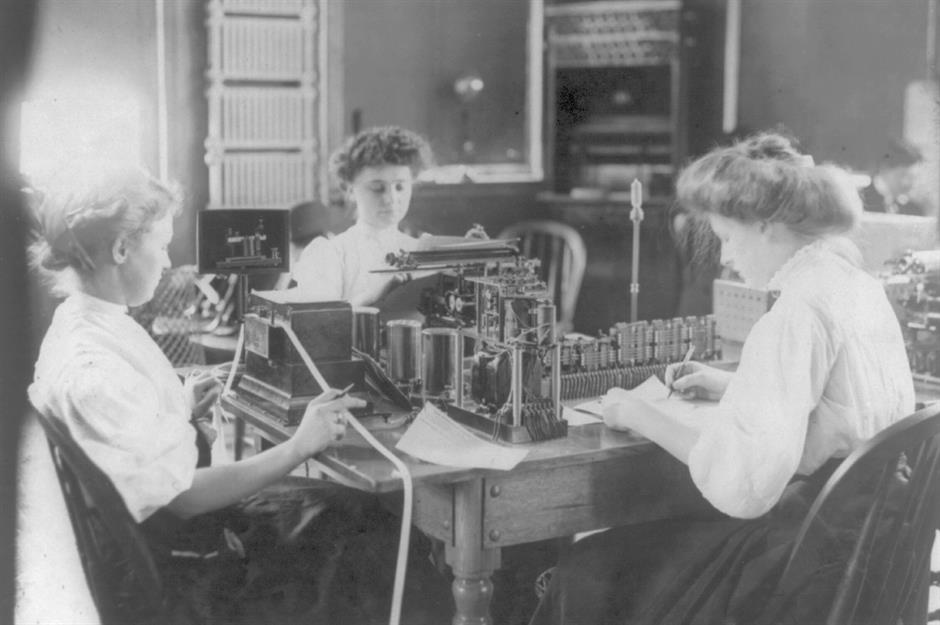

Telegraphy

The telegraphy industry flourished well into the 20th century. In 1945, 236 million domestic messages were sent, the most in a single year, it generated $182 million in revenues for the various telegraphy companies.

Ultimately, it was another 19th-century invention, the telephone, that led to the industry’s demise. In a perverse twist of fate, Alexander Graham Bell offered to sell the patent to Western Union for $100,000, but they decided to invest in teletypewriters (pictured) instead.

Horse-drawn carriage manufacturing

America's wagon and carriage industry began back in the colonial period and was served by small-time enterprises like this blacksmith shop in Fallston, Maryland. Vehicles were built to order, with little or no machinery and at a slow and steady pace using hand tools.

As roads improved and demand increased, small workshops began springing up in towns. Here, journeymen and apprentices worked under the guidance of a master craftsman to produce increasingly sophisticated vehicles.

Horse-drawn carriage manufacturing

The 1870s and 1880s saw the rise of enormous wagon and carriage factories that implemented new systems and technologies to mass produce vehicles at a more affordable price. While a good quality buggy cost roughly $135 in the 1860s, by 1880 the price had dropped to under $50.

In many ways, the horse-drawn carriage industry of the 19th century was not unlike the car industry today. Consumers were offered a dazzling array of carriages (pictured) across a variety of price points. Some, like Brewster & Company in Connecticut, were the Rolls Royce of their day, specializing in luxury carriages.

Sponsored Content

Horse-drawn carriage manufacturing

The rise of the automobile industry in the 1890s sounded the death knell of the US carriage industry. By the beginning of the 20th century, the horse and buggy had completely fallen out of favor with American families who preferred the ease and freedom of the new-fangled automobile.

At first, when automobiles were basically ‘horseless carriages,’ many of the skills needed to produce horse-drawn carriages were transferable. But as automotive technology improved and production lines became more sophisticated, age-old skills like wheelwrighting (pictured) became obsolete too.

Lumber

The lumber industry in the US began the moment English colonists set foot on North American soil. Demand for firewood and for shipbuilding in the old country had seen England’s forests decimated by the 13th century. America’s natural wood resources were a vital new supply source.

By the 1790s, the newly formed United States was already exporting more than 36 million feet (11 million meters) of pine boards and 300 ship masts each year. By 1830, Bangor in Maine was the world’s largest lumber-exporting port, moving a staggering 145 million feet (45 million meters) of board every year.

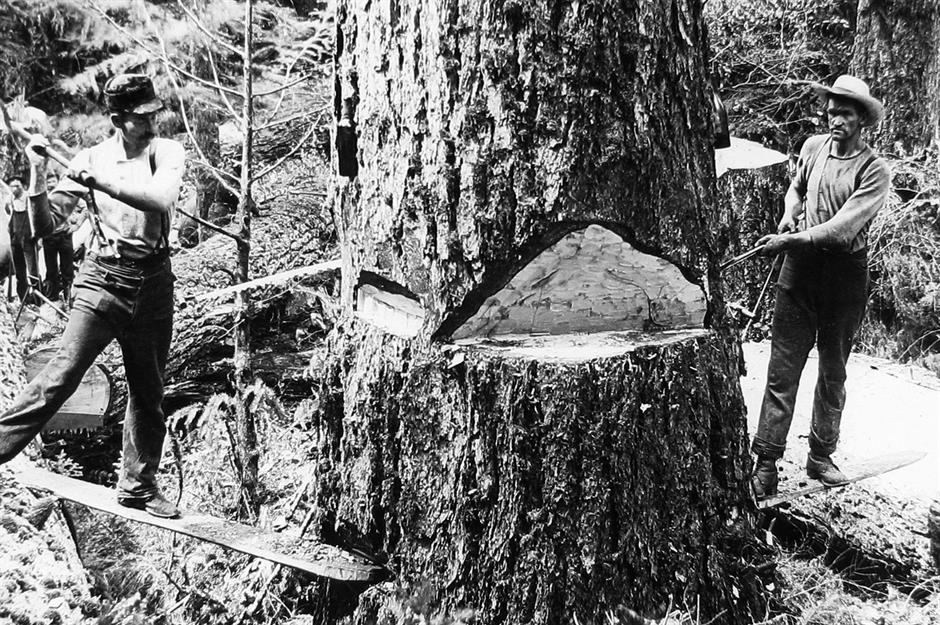

Lumber

The advent of steam-powered sawmills and the expansion of railways increased the efficiency of how the timber was processed and shipped about the country. The old-growth forests in Massachusetts, Maine, and New Hampshire were quickly exhausted and the industry moved on to the Midwest.

By 1900, timber supplies were dwindling in Idaho and the Midwest too, and loggers set their sights on the Pacific Northwest. By 1920, the US was producing 35 billion square feet (10.6bn sqm) of lumber. Thirty percent of it was coming from the Pacific Northwest.

Sponsored Content

Lumber

Timber, of course, is a finite resource. The insatiable demands of the industry created massive deforestation across the country and left behind devastated communities when the lumber industry moved on and took the boom times with it.

America is now the leading global importer of softwood lumber. What remains of the industry is more mechanized, consolidated, and tightly controlled by government regulations and restrictions.

Cigar manufacturing

In the 1830s, commercial cigar rolling came to Florida with Cuban immigrants starting small-scale operations in modest shacks like this one pictured in Key West. Then, in 1867, German immigrant and New York cigar manufacturer Samuel Seidenberg opened a Key West factory and the industry really took off.

Seidenberg used Cuban laborers to make authentic Cuban cigars in America and, in the process, avoided paying the high tariff levied against products from Havana. He could also circumvent the trade restrictions imposed on Cuban cigars by Spain as well.

Cigar manufacturing

In 1869, a successful cigar manufacturer from Cuba called Vicente Martinez Ybor followed Seidenberg’s lead and opened a factory in Key West. In 1885, he moved his operations to Tampa. Here, steamships could bring tobacco leaves directly from Cuba and a railway could distribute his products around the rest of the country.

At the height of the industry, there were 100 cigar factories in Key West, 150 in Tampa, and up to 100,000 workers traveling back and forth between Cuba and Florida each year.

Sponsored Content

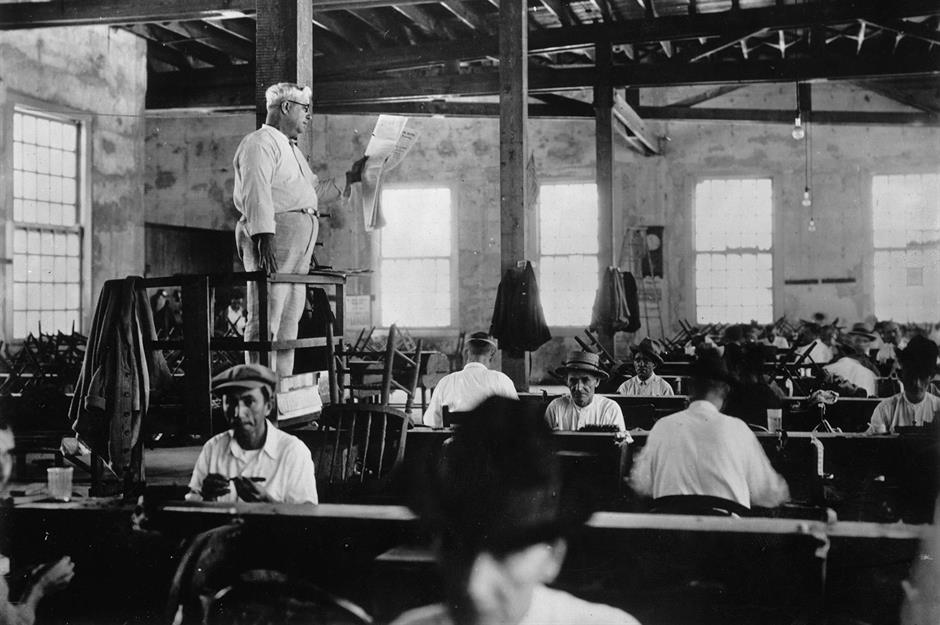

Cigar manufacturing

The close links to Cuba that helped create the industry would eventually bring about its demise. The factories were heavily unionized, just like the Cuban factories they were modelled on. A lector (pictured) had to be employed to read aloud to workers to help pass the time, and resistance to factory demands was commonplace.

When new machines were invented to turn out cigars much faster and cheaper, factory owners took the opportunity to streamline operations, before the hardships of the Great Depression finally killed off the demand for fine cigars altogether.

Textile manufacturing

Textile production was America’s first great industry and is credited with dragging the country into the Industrial Age. The first cotton spinning mill began operating in 1790 in Pawtucket, Rhode Island and within a decade there were 61 mills turning more than 31,000 spindles across New England.

Initially, Rhode Island and Philadelphia were the main manufacturing centers, but by 1820 the industry had spread south to Virginia and Kentucky. Initially, factory operations were limited to carding and spinning, but with the development of a workable power loom, all the production steps could take place under one roof.

Textile manufacturing

The mills transformed how people dressed, with clothing becoming much more affordable and allowing poorer people to copy the fashions of the well-to-do. It also created immense employment opportunities with people moving from farms and small towns to work in factories in the cities.

Child labor was also a feature of the textile industry at this time. They were paid 10-20% of what an adult would earn. They were easier to control and accepted punishment more easily. And they could fit into tighter spaces. Their small fingers were also perfect for unclogging spinning machines that were constantly becoming jammed.

Sponsored Content

Textile manufacturing

The American textile industry peaked in the first half of the 20th century, with factories producing fabrics, garments, and other textile goods, creating over 1.3 million jobs. The development of new synthetic fabrics in the 1950s also helped US textile manufacturing to stay on top of the world.

Within a few decades, however, new global supply chains saw manufacturers relocate to developing countries like China and India, where labor costs were considerably cheaper. Between 1997 and 2009, approximately 650 textile plants closed. By 2011, over 750,000 jobs had been lost.

Steamboat transportation

First invented in 1787, steamboats were an indispensable element of America's transport system until the end of the 19th century. They provided river transport for people and goods and, in the process, gave the young nation’s economy a massive boost.

Their design was as simple as it was revolutionary. Their shallow draught allowed them to navigate shallow waterways while their coal-powered steam engines gave them the ability to travel upriver and battle the strong currents of waterways like the Mississippi.

Steamboat transportation

The first regular steamboat service between New Orleans and Natchez in Mississippi began in 1812. By 1817, dozens of steamboats were plying the route. By the middle of the century, this number had swelled to more than 1,000.

Such was the extent of steamboat traffic and trade on the Mississippi River (pictured) that, by 1850, New Orleans had exceeded New York City in terms of shipping volume. The Louisiana city's outbound cargo accounted for more than half of the nation's total exports at this time.

Sponsored Content

Steamboat transportation

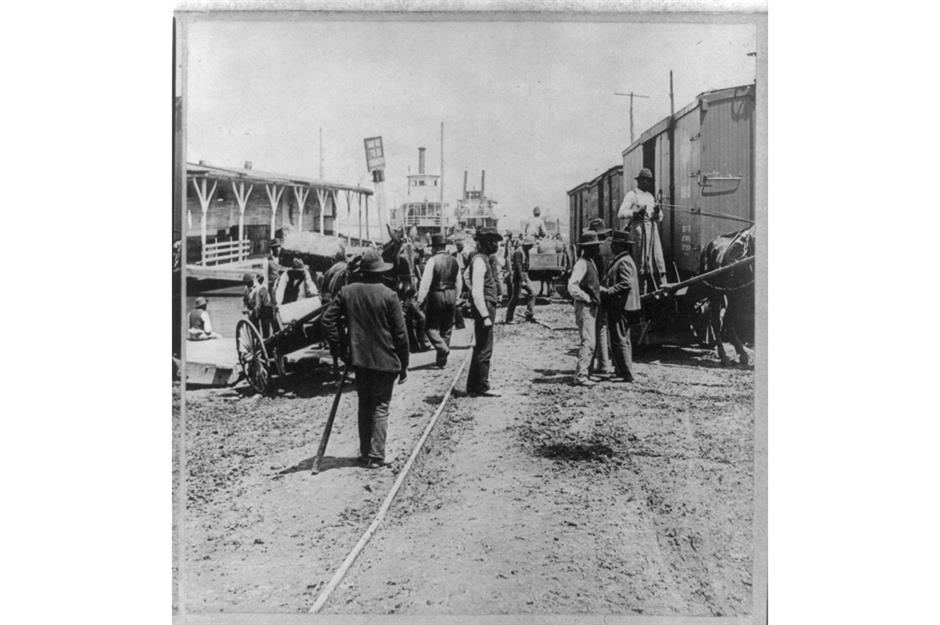

Steamboats played an important role in other parts of the country too, opening up routes between West Virginia in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west and from Minnesota in the north to Louisiana in the south.

By the 1870s, however, the rise of the railroads had made the demise of the steamboats inevitable. While the two modes of transport were often used in conjunction with each other, as seen here in Memphis, Tennessee, the reliability and efficiency of rail soon won out and the mighty steamboats retired.

Ice harvesting

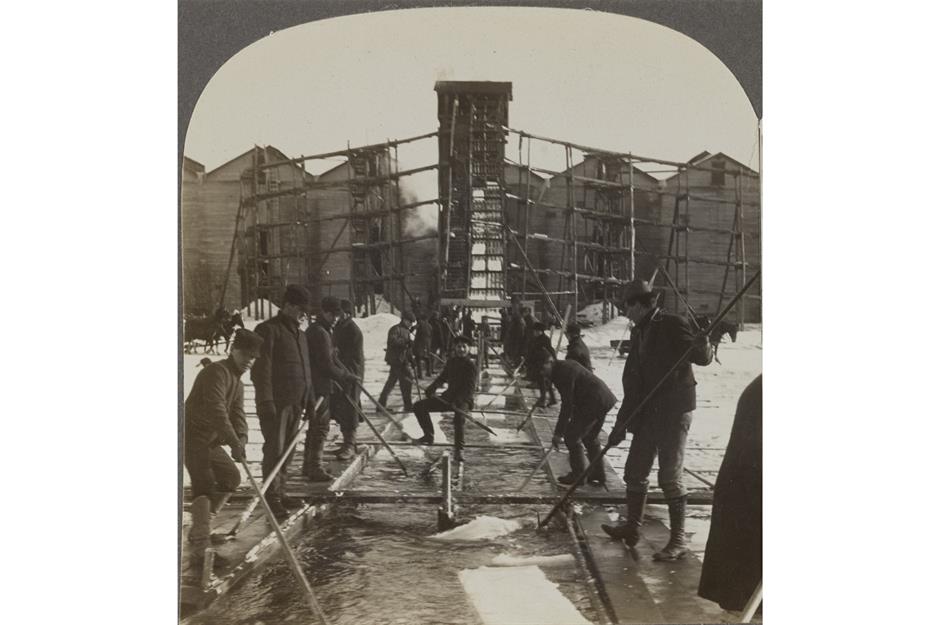

Before the invention of electrical refrigerators, one of the most effective ways for homes and businesses to preserve food was to use huge blocks of ice. Such was the demand that ice harvesting became one of the biggest industries in America in the 19th century.

Ice was treated as a cold-weather crop. Huge blocks of ice were cut from frozen lakes and rivers using giant hand saws (pictured), then floated to the shore where they were kept in sawdust in ice houses. The ice was then delivered to homes and businesses over the course of the year.

Ice harvesting

By 1886, 25 million tonnes of ice were cut and stored in the US annually. More importantly, it had become a thriving export industry too, second only to cotton. Blocks of this transparent gold were shipped as far afield as South America, India, and Australia.

Boston businessman Frederic Tudor was the first to ship American ice to warmer climes and subsequently became known as the ‘Ice King’. He built ice houses in the ports he shipped to, and by the time he died in 1864, he was worth the equivalent of $200 million in today’s dollars.

Sponsored Content

Ice harvesting

At the turn of the 20th century, the development of mechanical refrigeration equipment saw the industry drop to the ninth largest in the country. Export markets quickly dried up, and by the 1950s, the home market was obsolete too, with 80-90% of American homes owning electrical refrigerators.

However, the success of the Disney movie Frozen has seen places like Three Rivers Park in Minnesota introduce ice-harvesting activities for younger visitors. The film begins with a young Kristoff and his reindeer calf Sven trying their hand at ice harvesting, and it seems fans of the movie are keen to emulate them.

Coal mining

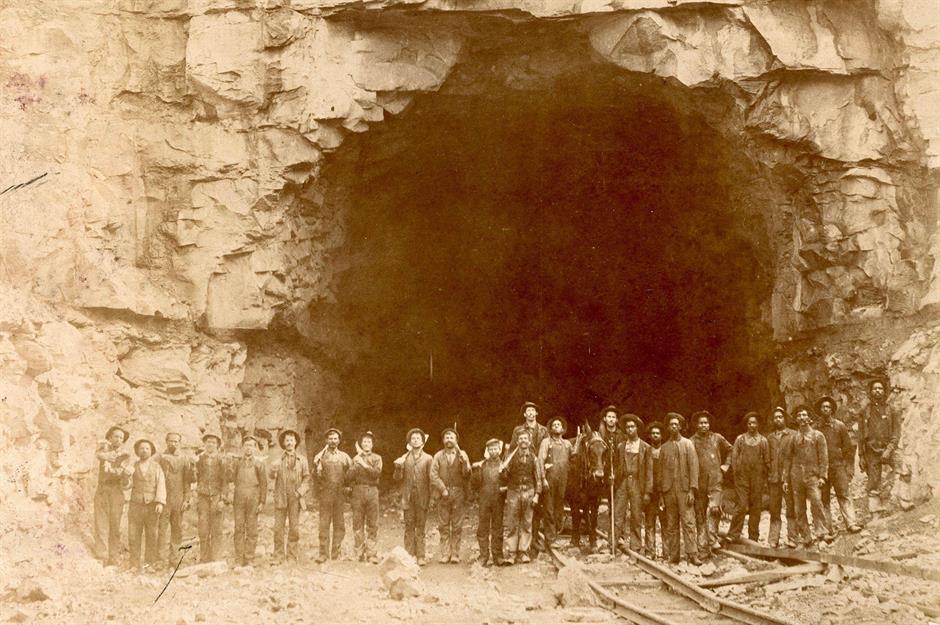

It's no exaggeration to say that the coal mines of the US fuelled American industry. First discovered near Richmond, Virginia in 1701 and commercially mined just 47 years later, the original black gold provided a cheap, efficient source of power for steam engines, furnaces, and forges across the country.

At first, coal was so plentiful in places like Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Ohio that laborers could simply ‘slope’ mine, collecting coal from exposed seams with picks and shovels. By 1900, however, demand was so great that miners went underground, like this group in West Virginia (pictured).

Coal mining

In the early days, coal miners worked close to the surface in horizontal drift mines that weren’t particularly dangerous. But as the demand for coal grew, especially in the big cities along the Eastern Seaboard, mines started going deeper – and more dangerous – in search of the precious resource.

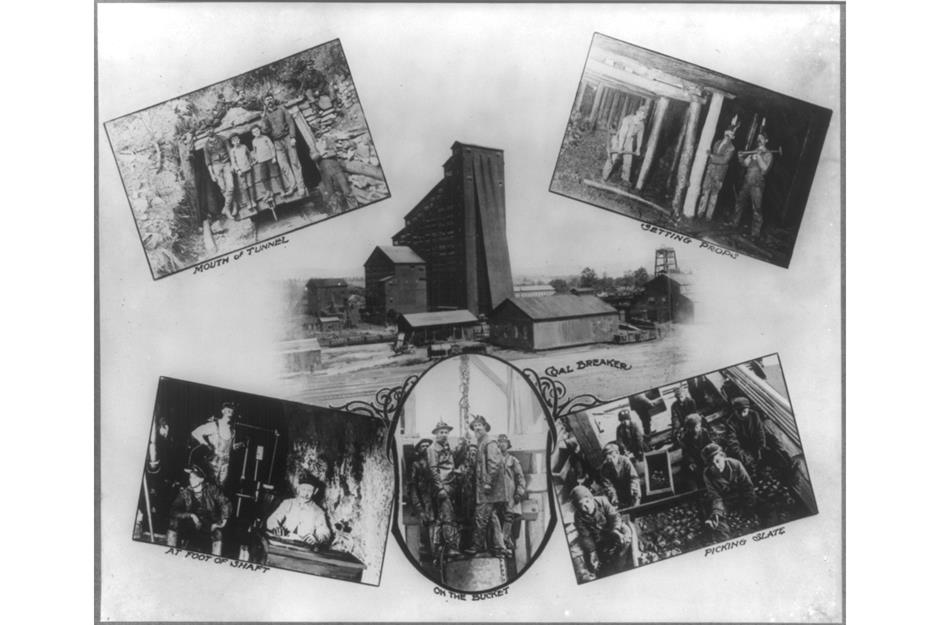

This montage of photographs shows the various activities involved in coal mining at the time, from entering the tunnels and setting shaft props to breaking coal, manning the buckets, and picking slate.

Sponsored Content

Coal mining

Coal mining was a labor-intensive industry and one that was not averse to using children, like these ‘breaker boys’, aged under 12 years old. But just as the industrial machines it fuelled became more sophisticated, so too did the tools used to extract it, meaning fewer workers were needed.

The decline of America's steel industry also hastened the decline of coal mining. While it continues in certain regions today, the rise of cleaner energy sources, environmental restrictions, and cheaper natural gas means that coal is no longer the cherished energy source it once was.

Timber rafting

During the early days of the American lumber industry, timber was sourced from remote forests, miles from civilization, let alone a timber mill. Roads were few and far between, so lumberjacks formed the logs they felled into huge rafts that were floated downriver to sawmills in bigger settlements.

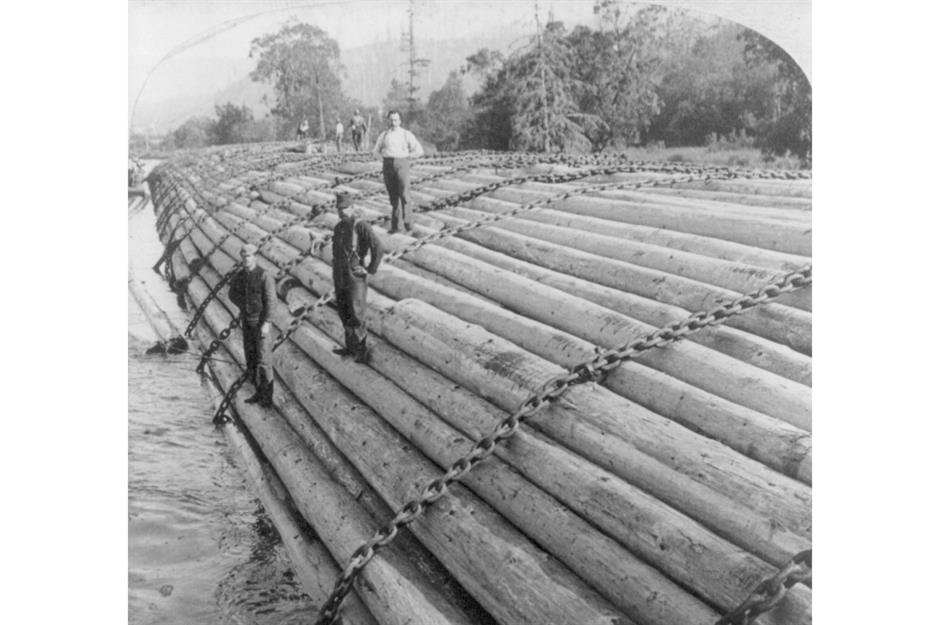

These lumber rafts were then coupled together like railway carriages, allowing each section to ‘break’ and negotiate bends in the rivers. Pictured here is a lumberjack forming a log raft in Tillamook, Oregon ahead of its trip downriver.

Timber rafting

The size of the rafts was determined by the speed and width of the river they were traveling along, but some reached lengths of over 2,000 feet (610m) and widths of over 160 feet (49m) and were made up of thousands of logs.

It also took a large crew to pilot them. A sweep man helped the raft negotiate bends in the river. Raft men used pike poles to push the raft off rocks, sandbars, and other snags.

Sponsored Content

Timber rafting

The journeys were often long. Timber felled in Wisconsin, for example, would be floated down the Mississippi toward New Orleans. Wannigans (kitchens) were built on rafts to feed the men four times a day, and tents were pitched for them to sleep.

By the late 18th century, the emergence of railroads and modern logging techniques brought about a rapid decline in timber rafting. Here, we see the beginning of the end, with a barge guiding a raft of logs through a drawbridge in Winona, Minnesota rather than a brave sweep man.

Automobile manufacturing

When the motor vehicle was invented in the late 1800s, the advances in horse-carriage manufacturing in America meant it was well-placed to be equally successful in this new, albeit similar enterprise.

The 19th century had seen the country develop a very particular system of manufacturing that focused on efficiency and the greater use of machine parts. In 1913, Henry Ford took that one step further with the introduction of the world’s first moving automobile assembly line (pictured), revolutionizing the nascent industry and ensuring America was a clear leader in the field.

Automobile manufacturing

Assembly lines required a greater initial outlay that saw many smaller car manufacturers fall by the wayside, even more so during the Great Depression. Those that remained, like Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler flourished. GM's CEO, Alfred P. Sloan Jr, once boasted that “in no year did the corporation fail to earn a profit.”

As demand for automobiles grew, so did the need for a large workforce, with Ford forced to hire 52,000 people to keep its production line going. Here we see 25,000 of those workers gathered in front of the Ford Motor Company plant around 1913.

Sponsored Content

Automobile manufacturing

The postwar years of the 1950s proved to be the apex of the US car industry, with workers enjoying lucrative union contracts as sales boomed. Life was good for workers like these ones checking Plymouth cars in 1959.

Storm clouds were gathering, however. As the war-torn economies of Germany and Japan bounced back, so did their car industries, introducing cheaper and more efficient models than the US was producing. Coupled with rising steel prices, persistent recessions, and an oil crisis in the 1970s, the US automobile industry, arguably America’s greatest ever, would never hit those heights again.

Now discover the famous American factories that turned to rust

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature